Nhà thơ

Nguyễn Chí Thiện

đã khuất núi

Dù thể xác lao tù héo khô muốn đổ

Dù đau lòng dưới năm tháng vùi chôn

Ta đã sống và không xấu hổ

Vì ta cứu giữ được linh hồn (NCT)

Dân tộc Việt Nam ngưỡng mộ thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện,

một chiến sĩ của sự "chí thiện", kiên cường

chống cái Ác, chịu 27 năm tù CS vì chí khí bất khuất,

phản kháng chế độ Việt cộng từ thời Nhân văn Giai Phẩm.

Nguyen Chi Thien, a Vietnamese poet,

died on October 2nd, aged 73

Oct 13th 2012 | from the print edition

The Economist

The Economist, October 13, 2012

THE poems were under his shirt, 400 of them. The date was July 16th 1979, just two days—he noted it—after the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille. Freedom day. He ran through the gate of the British embassy in Hanoi, past the guard, demanding to see the ambassador. The guard couldn’t stop him. In the reception area, a few Vietnamese were sitting at a table. He fought them off, and crashed the table over. In a cloakroom nearby, an English girl was doing her hair; she dropped her comb in terror. The noise brought three Englishmen out, and he thrust his sheaf of poems at one of them. Then, calm again, he let himself be arrested.

Thus Nguyen Chi Thien sent his poems out of Communist Vietnam. They were published as “Flowers of Hell”, translated into half a dozen languages, and won the International Poetry Award in 1985. He heard of this, vaguely, in his various jails. In Hoa Lo, the “Hanoi Hilton”, one of his captors furiously waved a book in his face. To his delight, he saw it was his own.

He was not strong physically. He contracted TB as a boy; his parents had to sell their house to pay for his antibiotics. Then since 1960, on various pretexts—contesting the regime’s view of history, writing “irreverent” poetry—he had done several long spells in prison and labour camp. Hard rice and salt water had made him scrawny and thin-haired by his 40s. Internally, though, he was like steel: mind, heart, soul. Sheer determination had forced him through the British embassy that day. In fact, the more the regime hurt him, the more he thrived:

They exiled me to the heart of the jungle

Wishing to fertilise the manioc with my remains.

I turned into an expert hunter

And came out full of snake wisdom

and rhino fierceness.

They sank me into the ocean

Wishing me to remain in the depths.

I became a deep sea diver

And came up covered with scintillating pearls.

The pearls were his poems. He kept his early efforts in a table-drawer where he found them later, the paper gnawed by cockroaches. The mind’s treasury was a safer place for them. It was also, for almost half his life, the only place he had. In prison he was allowed no pen, paper or books. He therefore memorised in the night quiet each one of his hundreds of poems, carefully revised it for several days, and mentally filed it away. If it didn’t work, he mentally deleted it. If it started to smell bad—like the one about Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam’s first Communist leader—he turned it into a stinging dart instead:

Let the hacks with their prostituted pens

Comb his beard, pat his head, caress his arse!

To hell with him!

Walking out to till the fields with his fellow prisoners, many of them poets too, he would recite his poems to them and they would respond with theirs. Some of them counted the beats on their fingers to remember. He never did; memory alone served him. It saved him, too.

After 1979 he spent the best part of eight years in solitary, in stocks or shackles in the dark. His poems became sobs, wheezes, bloody tubercular coughs. But in his mind he still set out fishing, and watched dawn overtake the stars. He sniffed the jasmine and hot noodle soup on a night street in Hanoi. He remembered his sister Hao teaching him French at six—what a paradise the French occupation seemed, in retrospect!—and went swashbuckling again with d’Artagnan and his crew. That way, he kept alive.

Drinking with Li Bai

A favourite prison companion was Li Bai (Lý Bạch), the great poet of eighth-century China. He would sup wine with him from amber cups, loll on chaises longues, watch pretty maidens weaving silk under the willow trees and the peach blossoms falling. He would talk to the moon with him and get wildly, romantically drunk.

There was a flavour here of his own careless youth, his teahouse years of girls and smoking. Both he and Li Bai had offended the emperor, mocked the education system, and been punished. But somehow the oppressions of the distant past seemed bearable. Not so the acts of Vietnam’s red demons, with their nauseating loudspeaker jingles about Happiness and Light.

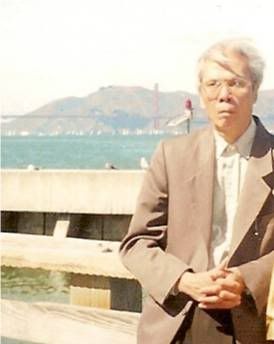

Out of prison, Li Bai-like, he dealt in rice brandy for a while, and tried to sell bicycle spokes. He could not make a go of it. From 1995 he managed to get shelter in America. He lived humbly in Little Saigon in Orange County, California, lodging with fellow countrymen. Green tea and smoking remained his chief comforts.

A flat cap or a fedora were his trademarks. He had nothing to share but his poems and his memories of fellow poets, whose cattle-trodden graves now dotted the hills around the labour camps. That, and his roaring hatred of the regime in his country, where his writings remained banned.

If people could see his heart, he had written back in 1964, during his first spell in prison, they would see it was an ancient pen and inkstand, gathering dust; or a poor roadside inn, offering only the comfort of an oil lamp. But it was also a paddy field waiting for the flood-rains of August,

So that it can overflow into a thousand waves,

White-crested ones that will sweep everything away!

Đăng trên tạp chí "The Economist"

October 13th, 2012, England

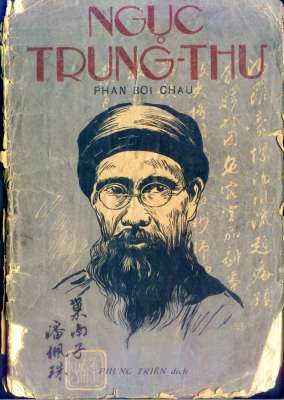

Nguyễn Chí Thiện &

Hoa Địa Ngục

Thi nhân vừa vĩnh biệt phong trần

Thân xác tàn theo bụi thế gian

Danh vẫn âm vang cùng tuế nguyệt

Hồn còn ẩn hiện với phong vân

Lao tù chẳng hủy tình dân tộc

Biệt xứ không màng chuyện giả chân

Mãi mãi dòng thơ Hoa Địa Ngục

Vẫn là đuốc sáng cho toàn dân

Nguyễn Đình Sài

(Washington

October 2, 2012)

Tôi Không Tiếc

Tôi không tiếc khi bị đời sa thải

Thân thể vùi, tan rữa, hóa bùn đen

Nhưng vần thơ trong đêm tối đê hèn

Cùng rệp muỗi viết ra mà bị mất

Tôi sẽ tiếc, khóc âm thầm trong đất

NCT, 1963

TIỄN BẠN NGUYỄN CHÍ THIỆN

Những hạt lúa làm thực phẩm cho Con Người

Phải chết dưới bùn mới trổ lá, đâm bông

Những mùa Xuân nồng ấm tươi hồng

Phải kết nụ bằng mùa Đông giá rét

Những tác phẩm vượt lên trên hết

Phải sản sinh bằng lửa tự Trái Tim

Những bài thơ cho Dân Tộc đắm chìm

Phải gọt dũa bằng máu xương tác giả

Những thi sĩ bị kẻ gian nguyền rủa

Lại chính là Tiếng Nói Lương Tâm

Nguyễn Chí Thiện, người ngục sĩ âm thầm

Đã trăn trở sống một đời kỳ dị

Đã uống cạn những nồng cay thế kỷ

Cười với tù giam, giỡn mặt Tử Thần

Đòn thù không màng, dù nát châu thân

Vẫn ngạo nghễ, lấy cùm đêm làm bạn

Ngày trơ xương, nhìn mặt trời nứt rạn

Mà khinh thường lũ bọ rệp vây quanh

Lấy mùa Đông tăng niềm nhớ mong manh

Lấy mùa Hạ để dâng cơn phẫn nộ

Dùng cơn đói làm bài thơ đồ sộ

Giấc ngủ xà lim nâng trí thức lên cao

Khi bình yên, thương một điếu thuốc lào

Lúc bệnh ốm, cười đợi chờ Thần Chết

Chỉ có hai điều, nhà Thơ cần hơn hết

Nhìn quê hương sạch bóng nội thù

Nhìn Việt Nam rực rỡ muôn thu

Và được chết nơi trận tiền, quê Mẹ

Trong tư cách một người không câu nệ

Hy sinh thân mình cho Tổ Quốc yêu thương..

Giờ đây! Giờ đây! Anh đã lên đường

Về đất Tổ, gặp những người Hùng muôn thế hệ

Chúng tôi, những chiến hữu của anh,

không thể ngăn giọt lệ

Tiễn anh đi mà tim thắt, đoạn trường

Xin lung linh của ánh nến, nén hương

Dẫn anh đến nơi Thiên Đường hoan lạc

Không còn những đau thương bàng bạc

Vẫn trường kỳ đeo bám Kiếp Phù Sinh…

Một lần cuối, xin cúi chào Anh,

Vĩnh Biệt!

Chu Tất Tiến

VIDEO:

Kim Nhung show

Tưởng nhớ nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kno0lXuKh0E&feature=channel&list=UL

VRNs (03.10.2012) – California, USA – Từ California, Chu Tất Tiến cho biết: “Vô cùng xúc động báo tin buồn: Nhà Thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, người Anh Hùng trong Thi Ca và Đời sống, người đã cống hiến cả cuộc đời mình cho đất nước Việt Nam, người đã thản nhiên chấp nhận 27 năm tù trong ngục tù Cộng Sản, vừa từ giã chúng ta lúc 7 giờ 17 phút sáng nay, ngày thứ Ba, ngày 02 tháng 10 năm 2012 tại Santa Ana, California (giờ Cali)”.

Tự điển bách khoa mở Wikipedia viết về nhà thờ Nguyễn Chí Thiện như sau: “Ông sinh 27 tháng 2 năm 1939 tại Hà Nội, là một nhà thơ phản kháng người Việt Nam. Ông từng bị nhà chức trách của Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa và của Cộng hòa Xã hội Chủ nghĩa Việt Nam bắt giam tổng cộng 27 năm tù vì tội “phản tuyên truyền”.

Ông được phóng thích ngày 28 tháng 10 năm 1991 và đến tháng 1 năm 1995 thì được xuất cảnh sang Hoa Kỳ”.

Nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã xuất bản:

“Tập thơ Hoa Địa ngục của ông xuất hiện ở hải ngoại vào năm 1980 sau khi tác phẩm này được lén đưa vào toà đại sứ Anh tại Hà Nội và được giáo sư Patrick J. Honey thuộc Đại học Luân Đôn (University of London), nhân chuyến đi Việt Nam năm 1979, mang được ra ngoài nước để phổ biến. Kèm trong tập thơ 400 trang viết tay này là lá thư mở đầu với lời ngỏ:

‘Nhân danh hàng triệu nạn nhân vô tội của chế độ độc tài, đã ngã gục hay còn đang phải chịu đựng một cái chết dần mòn và đau đớn trong gông cùm cộng sản, tôi xin ông vui lòng cho phổ biến những bài thơ này trên mảnh đất tự do của quý quốc. Đó là kết quả 20 năm làm việc của tôi, phần lớn được sáng tác trong những năm tôi bị giam cầm’.

Vì tập thơ không ghi tên tác giả, nên lần in đầu tiên năm 1980 do “Uỷ ban Tranh đấu cho Tù nhân Chính trị tại Việt Nam” phát hành tại Washington D.C. ghi tác giả là “Khuyết danh” hay “Ngục Sĩ” với tựa Tiếng Vọng Từ Đáy Vực. Năm 1981, ấn bản khác của báo Văn nghệ Tiền phong phát hành ở hải ngoại được ra mắt dưới tựa Bản Chúc thư Của Một Người Việt Nam.

Nhan đề Hoa Địa ngục được dùng đầu tiên năm 1984 khi Yale Center for International & Area Studies in bản tiếng Anh Flowers from Hell do Huỳnh Sanh Thông dịch. Sau này người ta mới biết đến tên Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Một số bài thơ trong Hoa Địa ngục đã được nhạc sĩ Phạm Duy phổ nhạc trong tập Ngục ca.

Cũng nhờ vì tập thơ này năm 1985 Nguyễn Chí Thiện đoạt giải “Thơ Quốc tế Rotterdam” (Rotterdam International Poetry Prize).

Trong khi ông bị giam cầm vì tên tuổi ông được biết đến nhiều, những hội đoàn như Tổ chức Ân xá Quốc tế (Amnesty International), Tổ chức Theo dõi Nhân quyền (Human Rights Watch) cùng những chính khách như Léopold Senghor (cựu tổng thống Sénégal), John Major (cựu thủ tướng Anh) và vua Hussein của Jordan từng lên tiếng tranh đấu cho ông được thả.

Năm 2006 tập thơ gồm hơn 700 bài của ông được đúc kết lại với đúng tên tác giả đã ra mắt độc giả người Việt hải ngoại một lần nữa và được đón nhận nồng nhiệt.

Tập thơ Hoa Địa ngục còn được dịch ra tiếng Đức với tựa Echo aus dem abgrund, tiếng Pháp: Fleurs de l’Enfer, và tiếng Hà Lan: Bloemen Uit de Hel. Cái tên này tác giả đã chọn ghi ở cuối lá thư đính kèm với tập thơ khi đột nhập tòa đại sứ Anh ở Hà Nội”.

Ngoài làm thơ, Nguyễn Chí Thiện còn viết văn. Nguyễn Chí Thiện được phóng thích năm 1991 và sang định cư ở Mỹ năm 1995. Năm 2001, tập truyện Hoả Lò của ông được nhà xuất bản Cành Nam ở Arlington, Virginia đem in cùng Tổ hợp Xuất bản miền Đông Hoa Kỳ phát hành năm 2001, rồi tái bản năm 2007.

Cũng trong năm 2007, tập truyện cùng với thơ ông được dịch ra tiếng Anh, nhan đề Hoa Lo/Hanoi Hilton Stories do Yale University Southeast Asia Studies xuất bản. Bản dịch có sự đóng góp của Nguyễn Ngọc Bích, Trần Văn Điền, Vann Saroyan Phan và Nguyễn Kiếm Phong.

Năm 2008 Hai Truyện Tù/Two Prison Life Stories, một tác phẩm song ngữ Việt-Anh được xuất bản ở Mỹ với sự cộng tác của Jean Libby, Tran Trung Ngoc và Christopher McCooey”. (PV.VRNs)

Tang lễ đưa tiễn cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện

Tang lễ đưa tiễn cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện

diễn ra ngày Thứ Bảy 6 tháng 10, 2012

tại Thánh Đường La Vang, miền Nam California,

Hoa Kỳ. Tro cốt của ông được an vị trên

tầng lầu sáu, Nhà Thờ Kiếng, là Nhà Thờ

Chánh Tòa Orange County, Nam California.

(Độc giả muốn biết thêm về tác phẩm Nguyễn Chí Thiện, "Trái Tim Hồng", có thể liên lạc trực tiếp với tác giả Trần Phong Vũ qua điện thoại (949) 485 – 6078 hoặc Email: tphongvu@yahoo.com)

Kết thúc Tuần lễ Tưởng Niệm

Nhân Húy Nhật đầu

cố Thi Sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện Tuần Lễ Tưởng Niệm cố Thi Sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện khởi đầu từ Thứ Bảy 21-9-2012 đã kết thúc long trọng hôm Thứ Bảy 28-9-2013 tại Trung Tâm Công Giáo Việt Nam Giáo Phận Orange, California.

Thánh Lễ:

Khởi đầu là Thánh Lễ đồng tế do Đức Giám Mục Mai Thanh Lương cử hành cùng quý LM Nguyễn Đức Minh, Vũ Hân, Nguyễn Thái từ 9 giờ đến 10 giờ sáng để cầu cho linh hồn Thomas More Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Đền Thánh đã không còn một chỗ trống khiến cả trăm giáo dân và đồng bào tham dự đã phải đứng dọc hai bên hành lang, tràn cả ra bên ngoài.

Trong bài thuyết giảng dịp này, LM Giám Đốc TTCG Nguyễn Thái nhắc lại cái cơ duyên thuở sinh thời thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã ba lần xuất hiện nơi đây. Trước hết là dịp giới thiệu thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục 2, tức là tác phầm Hạt Máu Thơ của ông năm 1996; Lần thứ hai là buổi ra mắt tác phẩm Hoả Lò năm 2001. Và lần thứ ba là năm 2005, cố thi sĩ nhận lời đọc và giới thiệu tác phẩm Giáo Hoàng Gioan Phaolo II Vĩ Nhân Thời Đại của nhà văn Trần Phong Vũ cũng tại hội trường Trung Tâm Công Giáo.

Sau khi gợi lại 27 năm đau thương, gian khổ mà cố thi sĩ đã trải qua trong các nhà tù cộng sản trên quê hương, trong phần kết thúc bải giảng thuyết, LM Nguyễn Thái nói:

“Trong đau khổ, tuyệt vọng, nhà thơ Phùng Quán đã tâm sự: “Có những giây phút ngã lòng, tôi đã vịn câu thơ mà đứng dậy.” Đối với cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, ông đã không chỉ “vịn câu thơ mà đứng dậy”, nhưng vịn vào linh hồn bất tử của thơ mà đứng dậy. Ông đã vịn vào sức mạnh của niềm tin nơi Đấng Tối Cao mà đứng dậy.

Ông đã ở tù ròng rã 27 năm trường, nhưng nhờ sức mạnh của thơ, của niềm tin vào linh hồn bất tử, vào sự nâng đỡ của Thượng Đế, nên ông vẫn bền lòng vững chí, như tên của ông là Chí Thiện. Với bản chất hiền lương, trong sáng, luôn hướng về Chân Thiện Mỹ, hướng về Đấng Chí Thánh, Đấng Chí Thiện như lời ông tự nhủ trong thơ:

“Nhà thơ ơi, phải biết,

Giữ linh hồn cho tinh khiết…

Nhà thơ còn phải biết,

Sống trong cõi đời như không bao giờ chết.”

Giống như hai môn đệ trên đường Emmaus, chính niềm tin vào Đức Kitô Phục Sinh đã giúp họ trở về trong hy vọng, thì đối với cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, cho dù cuộc đời ông phải chịu quá nhiều bất hạnh như lời Thánh Vịnh 89 diễn tả: “Tính tuổi thọ trong ngoài bẩy chục… Mà phần lớn chỉ là gian lao khốn khổ…” Nhưng với niềm tin vào Đấng Tối Cao, cố thi sĩ đã chấp nhận tất cả gian lao khốn khó và xem đó là sứ mệnh của mình:

“Nhưng số phận ta quá nhiều khắc nghiệt

Có lẽ Trời bắt ta phải chịu nhiều rên xiết

Để cho ta có thể hoàn thành công việc

Dùng lời ca ngăn hoạ đỏ lan tràn”

Hội Thảo:

Ngay sau Thánh Lễ là cuộc hội thảo về chủ đề “Nhìn lại Con Người, Cuộc Đời và những Di Sản Tinh Thần của cố Thi Sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện” khai diễn tại Hội Trường Trung Tâm trong gần ba tiếng đồng hồ. Cuộc hội thảo quy tụ ngót 300 đồng hương, trong số có những khuôn mặt trí thức tiêu biểu trong cộng đồng như quý giáo sư Toàn Phong Nguyễn Xuân Vinh, Lưu Trung Khảo và quý phu nhân, giáo sư Nguyễn Ngọc Bích (Washington DC), Trần Huy Bích, Nguyễn Thanh Trang (San Diego), Đỗ Anh Tài, Nguyễn Đình Cường, Dương Khải Hoàn, cựu Dân biểu Nguyễn Lý Tưởng, tiến sĩ Nguyễn Bá Tùng, tiến sĩ Lê Minh Nguyên, các bác sĩ Nguyễn Trọng Việt, Nguyễn Văn Quát, Trần Việt Cường, Trần Văn Cảo, cựu Nghị sĩ Trần Tấn Toan, kỹ sư Đỗ Như Điện, cựu đốc sự hành chánh Cao Viết Lợi, ký giả nhà văn Mặc Giao (Canada), nhà báo Huỳnh Lương Thiện (San Francisco), các nhà báo Khúc Minh, Vũ Thụy Hoàng, Trần Nguyên Thao, Đinh Quang Anh Thái, các nhà văn, nhà thơ Nguyễn Hải Hà, Anh Duy, Trần Thế Ngữ, các cựu sĩ quan QLVNCH thuộc mọi binh chủng như cựu Đại tá Chỉ huy trưởng Pháo binh Quân Đoàn 3 Lê Văn Trang, nguyên Thiếu tá Giám độc đài phát thanh Sàigòn Phạm Bá Cát, các cựu Sĩ quan Không quân Phạm Đình Khuông, Nguyễn Đức Chuyện, luật sư Trần Thanh Hiệp (Pháp), bà giáo sư Jean Libby, một trong những người bạn thân của cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện thuở sinh thời và đại diện các cơ quan truyền thông gồm hệ thống Truyền hình Free Việt Nam, các đài truyền hình VNA/TV, SET. VHN, Cơ sở Văn Hóa Lạc Việt, ký giả các nhật báo Viễn Đông, Việt Báo, Người Việt…

.Sau phần chào quốc kỳ Mỹ Việt, tưởng niệm các chiến sĩ và đồng bào đã xả thân vì chính nghĩa dân tộc, đặc biệt những tù nhân lương tâm đã chết hoặc còn bị đày ải trong các nhà tù cộng sản trên quê hương mà điển hình là cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, buổi hội thảo với chủ đề “Nhìn lại Con Người, Cuộc Đời và những Di Sản Tinh Thần của cố Thi Sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện” khởi đầu.

Vì phu nhân bị bạo bệnh bất ngờ phải vào cấp cứu trong bệnh viện, Tiến sĩ Bùi Hạnh Nghi từ Đức quốc không thể hiện diện nên bài thuyết trình của ông với nhan đề “Duyên kỳ ngộ nơi miền ngôn ngữ của Goethe” đã được ông úy thác cho nhà văn Mặc Giao trình bày giúp..

Theo Tiến sĩ Bùi Hạnh Nghi thì ngay từ đầu thập niên 80, khi nhà thơ nguyễn Chí Thiện còn bị đày ải trong ngục tù cộng sản ở quốc nội, ông đã được đọc những bài thơ tuyệt vời trong số 400 bài đầu của thi tập Hoa Địa Ngục dưới nhan đề xa lạ là “Bản Chúc Thư Của Một Người VN” . Từ đấy ông đã khám phá ra chân dung tác giả khi chưa ai biết là nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện dưới hai khía cạnh: một người anh hùng chống cộng quyết liệt và một thi nhân có tài.

Ông viết:

“Điều đầu tiên gây hứng thú cho tôi là nội dung chống cộng của tập thơ. Càng đọc tôi càng có cảm tưởng đã may mắn gặp một chứng nhân vẽ lên được một cách tường tận, đầy đủ hơn ai hết bức tranh toàn cảnh về tính chất bạo tàn của chế độ mà chính tôi đã chứng kiến và trải nghiệm phần nào trong thời niên thiếu lúc còn sống ở quê tôi Hà Tĩnh là nơi chính quyền cộng sản thống trị từ năm 1945. (…)

Ngoài những nhà tù chính hiệu, NCT còn phác họa cái nhà tù khổng lồ bao trùm trọn miền Bắc Việt Nam (và như ta biết sau 1975 miền Nam cũng đã trở thành nhà tù bao la rập theo khuôn mẫu miền Bắc). Như người thợ nhiếp ảnh tài tình, NCT đã thu trọn vào ống kính bức tranh ảm đạm của một xã hội nghẹt thở đắm chìm trong thấp thỏm lo sợ.”

Về giá trị thi ca trong Hoa Địa Ngục,

Tiến sĩ Bùi Hạnh Nghi nhận định:

“…đặc sắc của NCT không chỉ nằm trong đia hạt tố giác tội ác của cộng sản. NCT còn làm cho tôi bái phục hơn vì tài nghệ siêu cường trong địa hạt thi ca. Với tài nghệ đó ông đã cống hiến cho ta một tác phẩm mà văn học sử nước nhà sẽ mãi mãi lưu danh. Và trên trận tuyến chống bạo quyền, thi phẩm tuyệt vời của ông đã trở thành một hệ thống vũ khí vô cùng sắc bén. Thơ NCT không phải là một tác phẩm đấu tranh có tác dụng nhất thời mà mãi mãi sẽ là tiếng nói của con người muôn thuở.

Hủy diệt tự do tư tưởng, tự do ngôn luận, là đặc điểm của tất cả mọi thứ độc tài kim cổ và xưa nay đã có vô số người tố cáo. Nhưng bút pháp thần tình của NCT làm cho độc giả có cảm giác như sờ mó được cái độc hại, cái nguy hiểm của quái vật độc tài mà nanh vuốt là thủ đoạn "bỏ tù tiếng nói" và dùng miếng ăn như một thứ xích xiềng để nô lệ hóa.

Thoát thai từ một thực tế phũ phàng cay đắng, toàn bộ thơ NCT đã lấy thực tế đó làm đề tài duy nhất, nhưng lời diễn tả thì thiên hình vạn trạng nhờ vào bút pháp phong phú linh động, chuyển biến theo từng cảnh ngộ trong cuộc sống và theo từng nhịp đập của con tim.

NCT đã có công tạo những danh từ, những hình ảnh để phơi bày bằng nét bút sắc và đậm bộ mặt đa dạng của bạo lực. Ngôn ngữ của NCT đã có tác dụng của những quang tuyến diệu kỳ, của những "chiếu yêu kính" khiến cho hồ ly phải hiện nguyên hình và những ngụy trang lừa bịp không còn hiệu nghiệm. NCT vừa tố cáo tội ác trước công luận một cách hùng hồn vừa làm phong phú kho tàng ngôn ngữ chúng ta….”

Đọc lại những lời tâm huyết của cố thi sĩ kèm những vần thơ máu của ông khi liều mình đột nhập tòa Đại sứ Anh ở Hànội năm 1979 với khát vọng thiết tha là nó sẽ đánh động được lương tâm nhân loại trước những thảm cảnh mà dân tộc Việt Nam đang phải chịu đựng dưới chế độc độc tài CSVN, Tiến sĩ Bùi Hạnh Nghi tự thấy có trách nhiệm phải làm một cái gì để đáp lại tâm nguyện của nhà thơ. Và đấy chính là lý do thôi thúc ông để hết tâm huyết dịch thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục sang Đức ngữ. Được biết, hiện nay dịch phẩm này đã được dùng làm tài liệu giảng dạy cho học sinh bậc trung học ổ Đức.

Chấm dứt bài thuyết trình trong gần nửa tiếng đồng hồ,

diễn giả kết luận:

“Nhìn lại sự xuất hiện và sự đón nhận thơ NCT tại Đức và Áo, tôi thấy đó là một cuộc gặp gỡ, một cuộc trao đổi lạ kỳ. Quả là mối duyên kỳ ngộ của NCT nơi miền ngôn ngữ của Goethe, đệ nhất văn hào Đức quốc.”

Diễn giả thứ hai trong buổi hội thảo là Tiến si Trần Huy Bích với đề tài “Nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện và thời đại chúng ta”. Mở đầu bài thuyết trình, TS họ Trần đã nhấn mạnh tới nhân cách vĩ đại và tấm lòng bao dung, bác ái có một không hai của cố Thi sĩ. Ông cũng nhắc lại mối liên hệ mật thiết với nhà thơ qua mối giao tình sâu đậm với những người thân trong gia đình cụ cố Vũ Thế Hùng, người từng một thời ở tù chung với tác giả thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục.

Đề cập thái độ khoan hòa, độ lượng đặc biệt của nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, Tiến sĩ Trần Huy Bích đã gợi lại những phản ứng điềm tĩnh, chừng mục, coi nhẹ mọi sự của cố thi sĩ trước hành vi đầy ác ý của những kẻ cố tình xuyên tạc, bôi nhọ ông trong những năm tháng lưu đày nơi hải ngoại.

Sau khi đi sâu vào khía cạnh tình cảm trong thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện và những căn nguyên khiến đảng và nhà nước CSVN căm hận, đày ải nhà thơ trong suốt 27 năm dài, diễn giả nhắc lại trường hợp hai nhà thơ tiền bối là Đặng Trần Côn và Ôn Như Hầu Nguyễn Gia Thiều với những trường thi Chinh Phụ Ngâm Khúc và Cung Oán Ngâm Khúc, đối chiếu với cảnh ngộ của cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện và nội dung 700 bài thơ của ông để đi tới kết luận:

“…nỗi khổ của chinh phu, chinh phụ … trong CPNK (cũng như nỗi buồn khổ của người cung phi trong cung cấm) không thấm vào đâu so với nỗi khổ của người dân VN trong xã hội CS mà NCT vừa là người chứng kiến, vừa là nạn nhân. “

Ngoài hai tác phẩm của Đặng Trấn Côn và Nguyễn Gia Thiều, TS Bích còn trưng dẫn nội dung Văn Tế Thập Loại Chúng Sinh của thi hào Nguyễn Du để dẫn tới kết luận là tất cả những nỗi khổ đau, ngang trái mà người dân phải gánh chịu do cuộc tranh bá đồ vương thời Trịnh Nguyễn không thấm vào đâu nếu so sánh với những gì những người tù như Nguyễn Chí Thiện và đồng bào ta dưới chế độ bạo tàn cộng sản, và ông nhấn mạnh:

“Trách gì NCT không phải viết lên những câu như:

’Tôi muốn kêu to trong câm lặng đen dày

Cho nhân loại trăm miền nghe thấy.’“

Trước khi kết thúc, TS Trần Huy Bích đã trích dẫn nhận định sau đây của nhà văn Trần Phong Vũ trong “Nguyễn Chí Thiện, Trái Tim Hồng”, tác phẩm mới nhất của ông, do Tiếng Quê Hương vừa phát hành nhận dịp húy nhật đầu cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện:

“Tuy NCT đã vĩnh viễn ra đi, nhưng trong mắt và trong hồn tôi như vẫn hiển hiện hình ảnh cô đơn, cam đành, khiêm tốn và bất khuất của một con người mà khi sống cũng như khi chết đã để lại trong tâm hồn người quen biết ông những cảm tình quý mến không thể phai nhòa.” (TPV, trang 56).

Thuyết trình viên thứ ba trong buổi hội thảo là giáo sư Nguyễn Ngọc Bích, một trong những người đã giới thiệu thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục cũng như tập truyện Hỏa Lò của cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện với quần chúng độc giả nói tiếng Anh. Qua đề tài Nguyễn Chí Thiện và “vạn ngàn cơn thác loạn”, giáo sư Bích lần lượt vẽ lại những chặng đường đã dẫn đưa thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đi vào các vùng trời thế giới ngay từ giai đoạn đầu khi chưa ai biết tung tích tác giả là ai cũng như khi thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục vừa được ấn hành đầu thập niên 80 thế kỷ trước dưới những tên gọi khác nhau như Tiếng Vọng Từ Đáy Vực, Bản Chúc Thư Của Một Người Việt Nam.

Sau khi nhắc lại những nỗ lực không ngừng của nhiều dịch giả như Nguyễn Hữu Hiệu, Huỳnh Sanh Thông, Nguyễn Ngọc Quý, Bùi Hạnh Nghi nhằm giới thiệu thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện cho các độc giả ngoại quốc và sự đóng góp của nhiều nhạc sĩ như Phạm Duy, Phan Văn Hưng, Trần Lãng Minh, Xuân Điềm v.v…trong việc phổ nhãc nhiều bài thơ trong Hoa Địa Ngục. giáo sư Nguyễn Ngọc Bích cho biết thêm:

“Phần tôi, tôi đồng-hành với anh Nguyễn Chí Thiện từ khá sớm. Dịch anh từ lúc thơ của anh mới ra ngoài này…:

Tháng 7/1982, tôi có bài trong Asiaweek giới-thiệu thơ anh và dịch trên 10 bài.

Tháng 9/1982, Hội Văn-hoá VN tại Bắc-Mỹ của tôi in Ngục Ca / Prison Songs, dịch 20 bài thành hát được. Sau tăng bổ, cuốn này được Quê Mẹ ở Pháp in ra thành ba thứ tiếng. Cuối năm 1996, nhóm Hoa Niên ở Úc lại xin phép in cuốn song ngữ của tôi để phổ-biến ở Úc.

Tháng 10/1989, Văn Bút Miền Đông in ra tuyển-tập tiếng Anh War & Exile: A Vietnamese Anthology ("Chiến-tranh và Lưu đày: Tuyển-tập Thơ văn VN Hiện-đại") nhằm giới-thiệu văn-học VN với thế-giới nhân Hội-nghị Văn Bút Quốc Tế ở Montréal, Canada. Trong tập có giới-thiệu 30 trang thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Ít năm sau, Jachym Topol dịch thơ anh sang tiếng Tiệp là dựa vào mấy bản Anh-dịch của tôi….

Một tuần sau khi anh Thiện đến Mỹ, vào ngày 8/11/1995, anh được mời lên Quốc-hội điều trần về tình-trạng nhân-quyền ở VN (Nguyễn Ngọc Bích thông-dịch). Ngày 26/11/1995, anh ra mắt đồng-bào Thủ-đô Hoa-kỳ ở Trường Luật George Mason University trước một cử-toạ kỷ-lục, ngồi chặt cứng giảng-đường. Ngày 21/4/1996, ra mắt tập Anh-dịch song ngữ Hoa Địa Ngục / The Flowers of Hell do Nguyễn Ngọc Bích dịch gần như toàn-bộ Hoa Địa Ngục I (khoảng 5/6 trên 400 bài), cũng ở Trường Luật George Mason. Để chuẩn-bị cho chuyến đi sang Úc, tôi dịch thêm một tuyển-tập nhỏ (gần 100 bài) mang tên Hạt Máu Thơ / Blood Seeds Become Poetry (tức Hoa Địa Ngục II)….”

Để kết thúc bài tuyết trình, giáo sư Nguyễn Ngọc Bích lớn tiếng nói với cử tọa:

“Nguyễn Chí Thiện can đảm, điều đó khỏi nói. Nhưng nếu chỉ can đảm thôi thì ta có thể ngưỡng mộ anh nhưng anh vẫn không thể thành một nhà thơ lớn. Cái lớn của Nguyễn Chí Thiện nằm ở chỗ anh đánh trúng đối-tượng, từ những cái rất tầm-thường trong đời sống của người dân ("Bà kia tuổi sáu mươi rồi / Mà sao không được phép ngồi bán khoai?") đến cái khôi hài ("Miếng thịt lợn chao ôi là vĩ đại! / Miếng thịt bò lại vĩ đại bằng hai!"), ngộ nghĩnh ("Những thiếu nhi điển hình chế độ / Thuở mới đi tù trông rất ngộ. / Lon son không phải mặc quần / Chiếc áo tù dài phủ kín chân"), thương tâm ("Trên bước đường tù mà tôi rong ruổi / Tôi gặp hàng ngàn em bé như em.") để rồi cuối cùng điểm thẳng mặt kẻ thù ("Tôi biết nó, thằng nói câu nói đó")...

“…năm 1975, khi nghe thấy miền Nam tự do thất thủ, Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã thốt lên:

‘Vì ấu trĩ, thờ ơ, u tối,

Vì muốn an thân, vì tiếc máu xương

Cả nước đã quy về một mối

Một mối hận thù, một mối đau thương...

Miền Nam ơi, từ buổi tiêu tan

Ta sống trọn vạn ngàn cơn thác loạn!”

Ba vị được mời tham luận sau đó là bà Jean Libby, một người bạn thân của cố thi sĩ thuở sinh thời, luật sư nhà văn Trần Thanh Hiệp và một bạn trong nhóm Tuổi Trẻ Yêu Nước ở hải ngoại.

Xen kẽ những bài thuyết trình và tham luận trong buổi hội thảo là tiếng hát của Ban Tù Ca Xuân Điềm với những bài nhạc phổ từ thơ của cố thi sĩ. Ngoài nhiệm vụ chia sẻ vai trò MC với giáo sư Đỗ Anh Tài, dịp này nhà giáo Nguyễn Đình Cương cũng diễn đọc hai bài thơ Không Có Gì Quý Hơn Độc Lập Tự Do và Trái Tim Hồng của nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện.

Phát hành sách:

Lồng trong khuôn khổ buổi hội thảo là phần phát hành tác phẩm Nguyễn Chí Thiện, Trái Tim Hồng cuả nhà văn Trần Phong Vũ do tủ sách Tiếng Quê Hương xuất bản vào tuần lễ tưởng niệm nhân giỗ đầu tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục. Trong dịp này, ông Trần Phong Vũ đã được mời lên diễn đàn để nói qua về nội dung và căn nguyên thúc đẩy ông bỏ công thực hiện tác phẩm này trong vòng 9 tháng, thới gian kỷ lục cho một tập sách về một con người vĩ đại như cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện.

(Độc giả muốn biết thêm về tác phẩm Nguyễn Chí Thiện,

"Trái Tim Hồng", có thể liên lạc trực tiếp với tác giả Trần Phong Vũ qua điện thoại (949) 485 – 6078 hoặc Email: tphongvu@yahoo.com)

Trong bóng đêm đè nghẹt

Đã phục sẵn một mặt trời

Trong bóng tối không lời

Đã phục toàn cơn sấm sét

Trong lũ người đói rét

Đã phục sẵn một đoàn quân

Khi vận nước xoay vần

Tất cả thành nguyên tử!

NCT

Sẽ có một ngày con người hôm nay

Vứt súng,vứt cùm,vứt cờ,vứt đảng

Xoay ngang vòng nạn oan khiên

Về với miếu đường,mồ mả gia tiên

Mất chục năm trời bức bãnh lãng quên

Bao nhiêu thù hận tan vào hương khói

Sống sót chở về phúc phận an thân

Kẻ bùi ngùi hối hận,kẻ kính cẩn dâng lên

Này vòng hoa tái ngộ

Đặt lên mộ cha ông

Khai sáng kỷ nguyên mới

Tã trắng thắng cờ hồng

NCT

NGUYỄN CHÍ THIỆN ra đi

nhưng để lại “TRÁI TIM HỒNG”

Mặc Giao

Tính đến đầu tháng 10 - 2013, nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã từ bỏ cõi trần được một năm. Ông ra đi, để lại cho nhân gian một trái tim hồng, như hai câu thơ trăn trối của ông

Một trái tim hồng với bao chan chứa

Ta đặt lên bờ dương thế, trước khi xa

Nhà văn Trần Phong Vũ đã lấy lời và ý của hai câu thơ trên để đặt tên cho cuốn sách mới nhất của mình: “Nguyễn Chí Thiện, Trái Tim Hồng”, do Tủ Sách Tiếng Quê Hương ấn hành. Có lẽ tôi là một trong những người may mắn được đọc soạn phầm này rất sớm, dưới dạng bản thảo, trước khi được gửi sang Đài Loan in.

Trần Phong Vũ suy nghĩ, tìm tài liệu và viết cuốn sách trong vòng chưa đầy 10 tháng. Có người nghĩ Trần Phong Vũ là bạn tâm giao với Nguyễn Chí Thiện trên 10 năm, nếu viết xong cuốn sách về bạn trong 10 tháng thì cũng không có gì đáng lạ. Sự thật không giản dị như thế. Có mấy ai gom góp, lưu trữ tác phẩm, tài liệu, bằng chứng, hình ảnh của bạn để chờ bạn chết là viết thành sách liền đâu? Trong đôi giòng trước khi vào sách, chính Trần Phong Vũ đã thú nhận:

"Có thể vì một mối âu lo, sợ hãi thầm kín nào đó, tôi không muốn phải đối diện với nỗi đau khi một người thân vĩnh viễn chia xa. (…) hơn một lần trao đổi với nhau về cái chết một cách thản nhiên, coi như một điều tất hữu trong kiếp sống giới hạn của con người. (…) nhưng trong thâm tâm vẫn tự đánh lừa mình theo một cách riêng để cố tình nhìn cái chết dưới lăng kính lạnh lung, khách quan, nếu không muốn nói là vô cảm. Nói trắng ra chuyện chết chóc là của ai khác chứ không phải là mình, là người thân của mình!...

Dù là một người viết, nhưng suốt những năm tháng dài sống và sinh hoạt bên nhau, chưa bao giờ tôi nghỉ tới việc chuẩn bị, tích lũy những chứng từ, tài liệu, dữ kiện và hình ảnh cần thiết để viết về một khuôn mặt lớn như Nguyễn Chí Thiện, nếu một mai ông giã từ cuộc sống".

Vậy mà Trần Phong Vũ đã viết được một cuốn sách 560 trang, trong đó có 48 trang hình mầu, thêm phần Phụ Lục in những bài viết về Nguyễn Chí Thiện của 28 tác giả. Tác phẩm này là một tổng hợp có thể coi là đầy đủ về nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, người còn được gọi là "ngục sĩ" vì ông đã nếm cảnh ngục tù tổng cộng 27 năm trong số 56 năm ông sống trên quê hương.

Ông làm thơ rất sớm, và cũng đi tù rất sớm, trước tuổi 20, từ cuối thập niên 50, đầu thập niên 60 thế kỷ trước. Ông viết những vần thơ phẫn nộ khi nhìn tận mắt những cảnh “đào tận gốc trốc tận rễ” của cuộc cải cách ruộng đất và cảnh đầy đọa những người dính líu xa gần tới vụ Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm. Cuộc đời, thi tài và nỗi lòng của ông đã được Trần Phong Vũ trình bầy chi tiết. Tôi chỉ chia sẻ một số cảm nghĩ qua những tiết lộ và khám phá của Trần Phong Vũ liên quan đến Nguyễn Chí Thiện.

Khám phá đầu tiên là hành trình tâm linh của Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Tôi không muốn đem vấn đề tôn giáo ra tranh cãi với bất cứ ý định nào. Nhưng tôi buồn vì thấy đời độc ác qúa, tâm địa của một số người tối tăm, hẹp hòi quá. Một người làm thơ tranh đấu cho quyền của con người, đặc biệt con người Việt Nam, đã can đảm chấp nhận mọi đau khổ, thua thiệt, lãnh đủ thứ đòn thù, lúc gần chết ở tuổi 73 quyết định chọn một tôn giáo để theo, mà có những kẻ nỡ lòng lăng mạ ông “bị dụ dỗ lúc tinh thần không còn sáng suốt, để cho đám qụa đen cướp xác, cướp hồn (!)”

Qua những tiết lộ của Trần Phong Vũ, người ở bên ông trong 6 ngày cuối đời, người ta mới biết chính Nguyễn Chí Thiện ngỏ ý xin vào đạo lúc còn tỉnh táo. Đây không phải là một hành động bốc đồng trong một lúc khủng hoảng thần kinh, nhưng là kết qủa của một qúa trình tìm hiểu và suy nghĩ từ nhiều năm. Chính Linh Mục Nguyễn Văn Lý cho biết Linh Mục đã dậy giáo lý cho Nguyễn Chí Thiện tổng cộng trên một năm trời khi hai người cùng trong tù cộng sản.

Cụ Vũ Thế Hùng, thân sinh của LM Vũ Khởi Phụng hiện phụ trách giáo xứ Thái Hà, Hà Nội, bạn đồng tù với Nguyễn chí Thiện, đã nhận nhau là bố con tinh thần. Không kể những liên hệ và gặp gỡ khác, chỉ cần hai trường hợp này đã đủ để chứng minh Nguyễn Chí Thiện không thể bị dụ dỗ và u mê lấy một quyết định quan trong về tâm linh vào lúc cuối đời. xin hãy tôn trọng niềm tin của nhau. Hận thù tôn giáo là một tội rất lớn vì nó đã gây biết bao tang tóc cho nhân loại, và vi phạm quyền tự do cao qúy nhất của con người.

Về vấn đề tác giả và tác phẩm, có thể nói Trần Phong Vũ là người đầu tiên đã phân tích cặn kẽ về ý và lời của thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Tác giả đã dành nguyên một phần của cuốn sách để trình bầy vấn đề này. Sau đó ông đưa nhận xét:

"Trước hết, vì Nguyễn Chí Thiện là một nhà thơ có chân tài. Tài năng ấy lại được chắp cánh bay nhờ lòng yêu nước... Tất thảy đã trang bị cho nhà thơ một khối óc siêu đẳng, một cặp mắt tinh tế, một trái tim bén nhậy, biết thương cảm trước nỗi khổ đau của con người, biết biện phân thiện ác, chân giả giữa một xã hội điên loạn, gian manh, trí trá".

Nhận xét của Trần Phong Vũ cũng không xa với ý kiến của TS Erich Wolfgang người Đức mà ông trích dẫn trong chương 5 để lý giải cho câu hỏi: “Chiến sĩ, Ngục sĩ hay Thi sĩ” với mục tiêu trả lại cho nhà thơ vị trí đích thực của ông:

"Tình thương trong thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã chọc thủng tường thành tù ngục và đã vượt mọi chướng ngại của đồng lầy để đến với chúng ta ở Đức, ở Cali, Maderia, hay bất cứ nơi nào khác".

Ý thơ thì như vậy. Lời thơ, tứ thơ thì ra sao? Dĩ nhiên không thể tìm trong thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện một thứ "yên-sĩ-phi-lý-thuần" (inspiration) về tình ái hay cảm hứng khi đối cảnh sinh tình, như giữa cảnh trăng tà, sương khói mơ hồ, ánh đèn chài le lói trên sông, mà xuất khẩu thành thơ

Nguyệt lạc ô đề sương mãn thiên

Giang phong ngư hỏa đối sầu miên

Cảm hứng, ngôn từ trong thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện phải là những lời diễn tả sự đau sót, phẫn nộ của một nhân chứng trước những cảnh đầy đọa mà đồng loại và chính mình là nạn nhân. Thơ của Nguyễn Chí Thiện là những bản cáo trạng, đề tài không thể là viễn mơ, thi từ không phải là thứ gọt dũa cho đẹp. Tôi rất tâm đắc với Luật sư nhà văn Trần Thanh Hiệp khi ông nhận xét về thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện khi Nguyễn Chí Thiện còn đang ngồi tù ở Việt Nam:

"Thơ của ông (Nguyễn Chí Thiện) là chất liệu của văn học Việt Nam từ đầu hậu bán thế kỷ 20. Trong đổ vỡ, hoang tàn, ông đã tồn trữ được cả một kho ngôn ngữ. Trong cuộc giao tranh giữa những thế lực tiến bộ và phản động của một xã hội đang chuyển mình để thay đổi vận mạng, ông cho thấy người làm thơ nên chọn thái độ nào. Ông đã đóng góp bằng tác phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục vào cuộc tranh luận rất cổ điển giữa hai quan niệm về thơ thuần túy và thơ ngẫu cảm. Ông lảm thơ như Goethe đã nói từ đầu thập kỷ trước - 'Thơ của tôi là thơ ngẫu cảm, xuất phát từ thực tế và dựa trên thực tế. Tôi không cần đến những loại thơ bâng quơ' " (Nguyệt San Độc Lập, 25/5/1988 được tác giả họ Trần trích dẫn trong cùng chương 5 và đưa nguyên văn bài viết vào phấn phụ lục).

Đúng như vậy. Thơ của Nguyễn Chí Thiện không phải là thơ bâng quơ để chỉ phục vụ cái Mỹ, nhưng trước hết là thơ tranh đấu để đòi cái Chân và Thiện. Phải chăng chính vì thâm cảm được tấm lòng và ý chí bạn ông như thế -một tấm lòng, một ý chí đã có sẵn trong máu từ thuở nằm nôi-, nên tác giả Trần Phong Vũ từng viết: “…từ bên kia thế giới hẳn rằng song thân nhà thơ họ Nguyễn không thể khơng hài lòng vì đã chọn tên “Chí Thiện” đặt cho người con trai thứ của mình”.

Tản mác trong suốt 12 chương chính của tác phẩm, khi đề cập nỗi lòng của nhà thơ, Trần Phong Vũ đã nhiều lần kể lại những lời tâm sự mà Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã chia sẻ với ông. Trong chương thứ nhất viết về “Những ngày tháng lưu đầy” nơi hải ngoại của cố thi sĩ, nhà văn họ Trần cho hay vào một buổi chiều trên bãi biển Huntington Beach, Nam California, tác giả thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục âm thầm thú nhận khi mới đặt chân ra ngoài này ông tưởng đây là cơ hội để ông thực hiện giấc mơ thời trẻ, đó là được tự do sống một đời giang hồ, phiêu bạt.

Nhưng không, "nó chỉ là cái bề mặt che dấu nỗi uất hận bùng bốc trong tim mà không có cơ hội bộc phát, tương tự như dung dịch phún thạch cháy đỏ chất chứa trong lòng hỏa diệm sơn". Ai cũng hiểu cái uất hận đó là gì. Nhất là khi nó được biểu lộ bằng hành động và lời nói của Nguyễn Chí Thiện khi ông đi khắp nơi trên địa cầu để tố cáo sự tàn ác, vô nhân của chế độ cộng sản Việt Nam, tìm cách ảnh hưởng dư luận quốc tế và kêu gọi đồng bào chung tay lật đổ chế độ này để cứu dân cứu nước.

Ông có nỗi buồn bực khác không nói ra khi một số người xuyên tạc ông là Nguyễn Chí Thiện giả, được cộng sản Việt Nam đưa ra ngoại quốc để phá cộng đồng tỵ nạn. Chỉ cộng sản mới có lợi khi tung ra tin thất thiệt này, vì chỉ với một nghi ngờ không cần kiểm chứng, uy tín của Nguyễn Chí Thiện sẽ bị sứt mẻ, những lời tố cộng của Nguyễn Chí Thiện sẽ bị một số người bỏ ngoài tai.

Còn những người vu oan cho ông mà không phải là cộng sản thì sao? Chúng tôi không có thói quen thấy ai không đồng ý với mình thì lập tức cho mang cho họ dép râu, nón cối. Nhưng thú thật chúng tôi không thể hiểu nổi việc làm của những người đánh phá Nguyễn Chí Thiện khi trong thực tế nó còn tàn bạo hơn cộng sản. Cuối cùng chúng tôi chỉ dám tạm kết luận rằng ai biết được ma ăn cỗ? Ai biết được những âm mưu ẩn giấu bên trong việc tranh dành quyền lợi quanh nhân vật Nguyễn Chí Thiện? Ai rõ được những hận thù giữa các cá nhân và phe phái dùng câu chuyện Nguyễn Chí Thiện “thật/giả” để làm cái cớ tạo nên cảnh đánh đấm lẫn nhau?

Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã được nghệ sĩ Thanh Hùng, người cùng quê, quen biết nhau từ nhỏ xác nhận, đã được các bạn tù Nguyễn Văn Lý, Phùng Cung, Kiều Duy Vĩnh, Vũ Thư Hiên... thương mến, cảm phục, nhất là có người anh ruột Nguyễn Công Giân, trung tá trong quân lực VNCH, bảo lãnh sang Mỹ. Vậy mà họ vẫn nói đó là Nguyễn Chí Thiện giả!? Họ gạt bỏ luôn cả kết qủa giảo nghiệm chữ viết và nhân dạng/diện dạng của Nguyễn Chí Thiện trước và sau khi đi định cư tại Hoa Kỳ.

Họ cứ nằng nặc cho rằng đây là Nguyễn Chí Thiện giả do Hà Nội gửi sang Mỹ. Nếu đúng như vậy, chúng ta cầu cho cộng sản gửi ra hải ngoại thêm vài ngàn, thậm chí cả “mười ngàn Nguyễn Chí Thiện giả” cùng loại nữa như câu nói đùa của giáo sư Trần Văn Tòng, bào huynh liệt sĩ Trần Văn Bá khi tâm sự với tác giả Trần Phong Vũ trong một loạt Email trao đổi giữa hai người cuối năm 2008, trước và sau cuộc họp báo của cố thi sĩ ở khách sạn Ramada, nam California tháng 10 năm ấy. Nội dung những Email này đã được đưa vào phần phụ lục tác phẩm “Nguyễn Chí Thiện, Trái Tim Hồng”. Lúc đó chúng ta sẽ khỏi cần mất công làm công tác phản tuyên truyền cộng sản ở hải ngoại!

Một nỗi buồn khác của Nguyễn Chí Thiện là sức khỏe suy yếu. Sau bao nhiêu năm tù đầy, thiếu ăn, thiếu thuốc, bị hành hạ cả tinh thần lẫn thể xác, nên khi sang tới Mỹ, nhà thơ chỉ còn một cái đầu minh mẫn, thân xác thì vật vờ, "tim phổi nát bét cả rồi". Ông sống thêm được 17 năm ở hải ngoại là một phép lạ. Ông đã thổ lộ với Trần Phong Vũ:

"Tôi biết tôi sẽ không còn sống nổi tới ngày chế độ cộng sản tàn lụi đâu, dù căn cứ vào tình hình đất nước gần đây, tôi phỏng đoán sẽ không còn bao xa nữa".

Hy vọng ông sẽ sớm được chia niềm vui lớn với đồng bào, dù ông đang ở cõi khác.

Cuối cùng là tiết lộ khá lý thú về chuyện tình ái của Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Ai cũng thấy nhà thơ sống độc thân, thái độ nghiêm túc, lời nói chuẩn mực, hầu như không biểu lộ một tình cảm riêng tư với một bà, một cô nào, dù con số những người khác phái quý mến ông không thiếu. Có người nghĩ nhà thơ đã chán hay không biết đến tình yêu.

Sự thật, ông đã kể hết cho Trần Phong Vũ về những mối tình của mình. Không nói chuyện xa xưa, ngay những năm tháng cuối đời, Nguyễn Chí Thiện cũng có vài ba mối tình một chiều từ phiá nữ và một mối tình hai chiều mà ông ấp ủ trong lòng. Ông đâu phải là gỗ đá, lại là người viết văn, làm thơ, nên phải thuộc nòi tình, như thi hào Tản Đà từng thú nhận. Người tình hai chiều ở xa, muốn đến thăm ông tại Cali, ông không chấp thuận. Sao ông nỡ từ chối như vậy? Ông thổ lộ chỉ sợ khi gặp nhau, tình cảm sẽ đi xa hơn, ai biết được những gì sẽ xảy ra, hậu qủa chắc chắn sẽ buồn hơn là xa nhau mà thương nhau, nhớ nhau.

Lý do ông không muốn gắn bó với một người tình nào vì ông biết mình nhiều bệnh tật, thiếu sức khỏe, không chiều chuộng, chăm lo được cho người yêu, và không muốn tạo nên cảnh bẽ bang cho cả hai nguời, nhất là không muốn người yêu lại trở thành một thứ y tá bất đắc dĩ cho mình sau này.

Ngoài ra, ông còn ôm những nỗi niềm riêng trong lòng, không thể đem cả thân xác lẫn tâm hồn để yêu nhau. Vì vậy, đành phải xa nhau tuy lòng rất đau đớn. Rất may là ông đã kịp làm một bài thơ để âm thầm giãi bày cùng nàng, trước khi rời khỏi trần gian. Nói là âm thầm, vì bài thơ ngắn này ông tính giữ cho riêng mình và chỉ đọc cho tác giả họ Trần nghe trong những ngày tháng cuối đời mà thôi.

Tôi, một kẻ lạc loài

Một gã đàn ông đã xa lắm rồi

cái thời trai trẻ

Nhưng em vẫn yêu tôi bằng mối chân tình

mênh mông trời bể

Điều nghịch lý là tôi cũng yêu em

khi biết trước rằng mình không thể…

Và như thế

trong âm thầm

cam đành

lặng lẽ

chia xa!

Ngoài kia sương gió nhạt nhòa

trăng buồn

thổn thức

Đúng là một mối tình buồn!

Và ai dám nói đây là Nguyễn Chí Thiện “giả”, không biết làm thơ!?

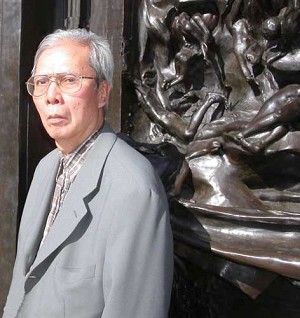

Được biết thêm về Nguyễn Chí Thiện qua cuốn sách của Trần phong Vũ, tôi càng thêm qúy mến cố thi sĩ, người tôi đã qúy mến ngay trong những lần gặp gỡ đầu tiên tại các thanh phố Edmonton và Calgary ở Canada, không lâu sau khi Nguyễn Chí Thiện đến Hoa Kỳ. Nhờ được giao công tác tiếp đón và giới thiệu nhà thơ trong các cuộc hội họp với đồng hương, tôi đã nhận ra lập trường, tài năng và nhân cách khác thường của tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục.

Sau đó, qua những lần gặp gỡ khác tại Hoa Kỳ, tôi càng thấy sự hy sinh chịu khó của Nguyễn Chí Thiện trong việc tham gia sinh hoạt với các tổ chức đấu tranh và các cơ quan truyền thông của đồng bào hải ngoại. Tấm thân già bệnh hoạn với những bước đi chậm chạp, nhưng khi đứng trước micro là giọng nói sang sảng, đanh thép vang lên, với những lập luận vững chắc, với những kinh nghiệm đã trải qua, tất cả dựa vào trí nhớ còn bén nhậy, không cần giấy ghi chi tiết. Nguyễn Chí Thiện là một chiến sĩ đã chiến đấu cho đến lúc hơi tàn lực cạn.

Với cuốn “Nguyễn Chí Thiện, Trái Tim Hồng”, Trần Phong Vũ đã làm một việc cần thiết và hữu ích. Cần thiết vì ông đã dành hết tâm lực cuối đời để ghi lại được những di sản tinh thần quý giá của một nhà thơ chiến sĩ, đã hy sinh trọn tuổi thanh xuân để làm nhân chứng cho sự tàn bạo của cộng sản và để đấu tranh nhằm giải thoát quê hương, đồng bào khỏi sự tàn bạo ấy. Hữu ích vì tấm gương của Nguyễn Chí Thiện cần phải được phổ biến bây giờ và mai sau cho nhiều người, nhất là người trẻ, để họ đừng chỉ nghĩ đền mình, biết sống chan hòa với mọi người như cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, biết hy sinh tranh đấu cho sự thật, công lý và những giá trị thiêng liêng của con người.

Trần phong Vũ đã vất vả hoàn thành tác phẩm trong một thời gian kỷ lục, nhưng sau đó chắc ông vui vì đã làm được một việc ý nghiã để tạ lòng người tri kỷ. Trần Phong Vũ đã viết hồi ký thay cho Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Một thứ hồi ký không xưng hô ở ngôi thứ nhất. Nhưng ở ngôi thứ ba.

Cám ơn tác giả họ Trần, và ở cõi khác, hẳn rằng nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện không thể không ngậm cười vì những gì ông gửi gấm trong bài Trái Tim Hồng, được sáng tác vào năm 1988, sau 24 năm trong nhà tù cộng sản, khi thân xác ông hoàn toàn suy kiệt để trong một phút cảm khái đã viết nên bài thơ, như một lời trối gửi lại những đồng bào còn sống trước khi trở về với cát bụi.

“Ta có trái tim hồng ,

Không bao giờ ngừng đập

Cam giận, yêu thương, tràn ngập xót xa

Ta đang móc nó ra

Làm quà cho các bạn

Mấy chục năm rồi

Ta ngồi đây

Sa lầy trong khổ nạn

Như con tàu vượt trùng dương mắc cạn

Mơ về sóng nước xa khơi

Khát biển, khát trời

Phơi thân xác trong mưa mòn, nắng rỉ

Thân thế tàn theo thế kỷ

Sương buồn nhuộm sắc hoàng hôn

Ký ức âm u, vất vưởng những âm hồn

Xót xa tiếc nuối!

Ta vẫn chìm trôi trong dòng sông đen tối

Lều bều rác rười tanh hôi!

Hư vô ơi, cập bến đến nơi rồi!

Cõi bụi chờ mong chi nữa!

Một trái tim hồng với bao chan chứa

Ta đặt lên bờ dương thế… trước khi xa!

(1988 - Hoa Địa ngục –

trang 348/349, Tổ hợp Xuất bàn Miền Đông)

Mặc Giao

Calgary, Canada một đêm cuối tháng 8 năm 2013

Liệt sĩ Trần Văn Bá là con trai cố Giáo sư Trần Văn Văn, em Giáo sư Trần Văn Tòng. Ông Bá từng là người đầu tiên sau tháng tư năm 75 bỏ Pháp về Việt Nam với chí nguyện thành lập một lực lượng chống lại chế độ cộng sản, nhưng bất hạnh ông đã bị CS bắt và xử tử hình năm 1985. Ông được Sáng hội Tượng đài Nạn nhân Chủ nghĩa Cộng sản tại Mỹ truy tặng huy chương Tự Do Truman–Reagan năm 2007.

TIỄN BƯỚC ANH, NGƯỜI THƠ BẤT KHUẤT

(Tiễn chân Ngục sĩ NGUYỄN CHÍ THIỆN, người Thi Sĩ Đấu Tranh cho một Việt Nam Không Cộng Sản, từng bị bạo quyền Việt cộng nhốt tù 27 năm, vừa bỏ lại đau thương của dâu biển kiếp người để về nơi bình an miên viễn sáng ngày 2/10/2012 tại miền đất tạm dung, Nam California, Mỹ Quốc) Người bạn gọi báo tin anh vừa mất

Tôi thấy lòng mình chùng xuống, mênh mông

Anh đi rồi à ? Người Thơ Bất Khuất ...

Để lại dòng thơ máu lệ Lạc Hồng !

Ôi những dòng thơ viết trong ngục tối

Xiềng xích, gông cùm, đói, bịnh, hờn đau

Đấy, tội ác của tà quyền Hà Nội

Bán nước, giết dân, luồn cúi Nga-Tàu !

Tôi đọc thơ anh, lòng đau muối xát

Thương quá tài năng, xót quá phận người

Hai muơi bảy năm hung đồ chà đạp

Thơ vẫn hiên ngang, hào khí tung trời

Thơ đã bay cao vang rền bốn cõi

Lay gọi người trúng độc tỉnh cơn mê

Giục nhân loại, lương tâm, lên tiếng nói

Về một Việt Nam thảm khốc, ê chề ...

Đã sắp rồi anh ngày quê quang phục

Dân vùng lên đòi quyền sống con người

Lấy máu Tiên Rồng rửa hờn quốc nhục

Chính nghĩa, cờ Vàng rực rỡ muôn nơi

Sáng hôm nay tôi nghe tin anh mất

Bỏ lại đau thương dâu biển kiếp người

Anh biết đấy, khi buồn vui chất ngất

Bút sẽ thành thơ chảy với dòng đời

Tôi viết bài thơ tiễn anh về đất

Lòng đất hiền, anh ngủ nhé, ngàn thu ...

Thôi, đã hết, đời không còn oan khuất

Chỉ còn Thơ chiến đấu diệt quân thù.-- Ngô Minh HằngChiều tháng Sáu (thơ: Nguyễn Chí Thiện; nhạc: Phan Văn Hưng), qua tiếng hát Phan Văn Hưng (audio nhạc)

Từ ngày qua Mỹ đến nay nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện được mời đi nói chuyện khắp nơi trên thế giới để tố cáo tội ác CSVN, tiếp xúc nhiều với các chính trị gia, các đảng phái, các vị trong giới lãnh đạo…đâu đâu ông cũng được đón tiếp niểm nở.

Ông được Nghị Viện Quốc Tế các Nhà văn (International Parliament of Writers) mời đến nghỉ ở miền Ðông nước Pháp, đài thọ cho ông qua hai năm liên tiếp chỉ để "ngồi viết cái gì mà ông muốn" và tập truyện ngắn Hoả Lò ra đời từ đó.

Nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện được vinh danh và

nhận lãnh nhiều giải thưởng quốc tế như :

-Giải thưởng Thơ Rotterdam Hoà Lan (1984),

-Giải thưởng "Tự Do Ðể Viết (" Freedom To Write")

của Trung tâm Văn Bút Hoa Kỳ,

- Giải Nhân Quyền của tổ chức Human Rights Watch (1995),

Và tên tuổi ông được ghi vào từ điển "Who's Who in

Twentieth- Century World Poetry" in ở Anh Quốc

tháng 2-2001 và lần 2 ở Ðức năm 2002.

Thơ ông đã được dịch sang nhiều thứ tiếng, được các văn thi sĩ quốc tế ngợi khen trong đó đa số là các nhà văn trước kia sống dưới chế độ CS như Paul Goma(Lỗ Ma Ni), Pierre Kende (Hung Gia LợI),Vladimir Maximov(Nga), Leonid Plioutch (Ukraine), Alexandre Smolar (Ba Lan), Pavel Tigrid (Tiệp Khắc), Erich Wolfgang Skwara (Ðức)

Và đặc biệt hơn cả là bản dịch ra tiếng Ðức của giáo sư Tiến sĩ Bùi hạnh Nghi đã được đưa vào chương trình "Ðọc Sách hay" trong các trường trung học đệ nhị cấp ở tiểu bang Bayern Ðức Quốc.

Ngoài ra trong số này còn có 14 bài thơ cũng đưọc Gunter Mattitsch, nhạc sĩ người Áo phổ nhạc trình diễn trước công chúng Áo ở Klagenfurt ngày 20-10-1995.

Theo tại liệu trong Hoa Ðịa Ngục

1&2 xuất bản năm 2006)  AUDIO ĐẶC BIỆT GIỖ 100 NGÀY NGUYỄN CHÍ THIỆNNhà văn Trần Phong Vũ

AUDIO ĐẶC BIỆT GIỖ 100 NGÀY NGUYỄN CHÍ THIỆNNhà văn Trần Phong Vũ nói về khí phách và tâm tư

thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, qua nội dung và ý nghĩa

những bài thơ làm trong nhà tù cộng sản khổ nhục.

Bài nói chuyện trên PALTALK thực hiện vào Chúa Nhật

ngày 6 tháng 1, 2013 nhân Giỗ 100 ngày cố thi sĩ

Nguyễn Chí Thiện khuất núi, ra đi về cõi miên viễn.

to listen:

To download

"Quan, Quần, Hưng, Oán”

trong thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện

Một số tổ chức đã phối hợp thực hiện buổi lễ tưởng niệm thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện tại phim trường đài Truyền Hình VHN từ 2 đến 4 giờ Chúa Nhật, ngày 06-01-2013. Buổi tưởng niệm đã

được truyền hình trực tiếp.

Trần Phong Vũ

Nhân Giỗ 100 ngày cố Thi Sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, bàn về tôn chỉ “Quan, Quần, Hưng, Oán” trong thơ ông

Trong Lời Tựa thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục do Tổ Hợp Xuất Bản Miền Đông, Hoa Kỳ ấn hành năm 2006, cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện viết:

“Khổng Tử có lời luận về thơ như sau: ‘Thi khả dĩ quan, khả dĩ quần, khả dĩ hưng, khả dĩ oán’, nghĩa là thơ có khả năng giúp ta biết nhìn nhận, biết tập hợp, biết hưng khởi, biết oán giận’. Suốt cuộc đời làm thơ, lúc nào tôi cũng theo tôn chỉ ‘Quan, Quần, Hưng, Oán’ đó, vì tôi nghĩ nó tóm tắt khá đủ về chức năng của thơ”.

Với thái độ khiêm tốn cố hữu – và cũng có thể do ý hướng của một nhà thơ luôn cầu toàn – tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục viết tiếp: “Nhưng do năng lực giới hạn, thơ tôi chưa đạt được bốn tiêu chuẩn trên.”

Mời độc giả cùng người viết, đọc và tìm hiểu thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện để coi tác giả đã đạt được đến đâu qua tôn chỉ Quan, Quần, Hưng, Oán theo lời bàn của Khổng Phu Tử

Thi khả dĩ quan

Thơ có khả năng giúp ta biết nhìn nhận. Nhìn nhận cái gì nếu không là những hình tượng của người, vật hoặc sự việc diễn tả trong câu thơ hoặc toàn bộ bài thơ, từ dấu tích bề ngoài cho tới những ý tưởng hàm ngụ bên trong và đàng sau người, vật hoặc sự việc.

Đan cử bài “Một tay em trổ…” trang 211 Hoa Địa Ngục:

“Một tay em trổ: Đời xua đuổi!

Một tay em trổ: Hận vô bờ!

Thế giới ơi, ngươi có thể ngờ

Đó là một tù nhân tám tuổi!

Trên bước đường tù, tôi rong ruổi

Tôi gặp hàng nghìn em bé như em!”

(1971)

Qua sáu câu thơ ngắn ngủi trên đây, bằng cặp mắt quan sát và bằng khối óc suy tư, -với tầm hiểu biết sơ đẳng-, người đọc nhìn thấy và nhận ra ngay dáng vẻ bề ngoài dị thường của một em bé với những vết chàm mang tự dạng trên hai tay. Một bên là ba chữ Đời xua đuổi, và bên kia: Hận vô bờ! Tác giả thảng thốt kêu lên: liệu thế giới ngoài kia có thể ngờ rằng đấy chính là nhân dạng của một tù nhân lên tám?

Rồi qua hai câu cuối, tác giả cho người đọc biết thêm: trên bước đường rong ruổi lăn lộn hết nhà tù này sang nhà tù khác dưới chế độ cộng sản trong ngót ba thập niên, ông đã từng bắt gặp hàng nghìn tù nhân “con nít” như thế!

Nhìn dáng vẻ bề ngoài dị dạng với nét chữ xâm trên tay của em bé tù nhân, người đọc không thể không nêu lên câu hỏi: tại sao lại đời xua đuổi? và tại sao lại hận vô bờ? Rồi ngay lập tức câu trả lời hiện ra trong trí: xã hội, chế độ đã xua đuổi, trù giập em. Từ đấy đã để lại trong em mối hận thù chất ngất khôn nguôi! Xa hơn, trong trí người đọc thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện còn nảy sinh biết bao câu hỏi về nguyên nhân, hệ quả của những thế hệ trẻ thơ bất hạnh đang kéo dài kiếp sống vất vưởng trên đất nước ta hôm nay. Nó là hậu quả tất nhiên của một xã hội băng hoại, một nền giáo dục suy đồi xuống giốc tại Việt Nam mà qua những thông tin được gửi ra hàng ngày ai cũng biết.

Năm 1966, tức 5 năm trước đó, trong bài “Những thiếu nhi…” trang 139-140, Hoa Địa Ngục, tác giả viết:

“Những thiếu nhi điển hình chế độ

Thuở mới đi tù trông em thật ngộ!

Lon xon không phải mặc quần

Chiếc áo tù dài phủ kín gót chân

Giờ thấm thoát mười năm đã lớn

Mặt mũi vêu vao, tính tình hung tợn

Mở miệng là chửi bới chẳng từ ai

Có thể giết người vì củ sắn, củ khoai!

(1966)

Vẫn chỉ là những nét chấm phá hình ảnh của một em nhỏ sớm sa chân vào vòng lao lý trong chế độ cộng sản Việt Nam. Khác chăng là ở đây nhà thơ đã cho người đọc thấy rõ những đổi thay từ tính khí tới nhân dáng bề ngoài của một em bé dễ thương, ngộ nghĩnh –cho dẫu đấy là cái dễ thương, ngộ nghĩnh “cười ra nước mắt” của những ngày đầu mới chân ướt chân ráo bị đẩy vào tù, còn ở truồng với “chiếc áo tù dài phủ kín gót chân”, cho tới khi trở thành một thanh niên hung hãn, bặm trợn, máu lạnh, có thể chỉ vì miếng khoai, củ sắn mà biến thành kẻ sát nhân, hậu quả của 10 năm được đảng và chế độ cộng sản đào luyện trong gông cùm, sắt máu!

Với cách diển tả cô đọng, hiện thực, chỉ trong 8 câu thơ ngắn, Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã vẽ ra trước mắt người đọc một chuỗi những hoạt hình linh động đầy kịch tính. Trong số 700 bài thơ trong toàn tập thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục, người đọc bắt gặp không ít những lời thơ đơn sơ, mộc mạc, dễ tiếp nhận như hai bài trích dẫn trên đây. Chi tiết này đã được chính ông xác nhận trong bài đọc Tuyển Tập thơ văn của người viết(1) khoảng ngót một tháng trước khi ông phải vào bệnh viện. Đây là bài viết duy nhất cùng loại và là bút tích cuối cùng của tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục trước khi từ giã cõi đời.

Nguyễn Chí Thiện viết:

“Tôi là người làm thơ. Nhưng hầu hết thơ của tôi được ghi lại trong cảnh tù đày, mang nặng những đau thương, uất nghẹn của thân phận con người (…) Nó là những hiện thực trần trụi, đơn sơ, không có tu từ văn chương, đọc thấy ngay, hiểu ngay…”

Thi khả dĩ quần

Thơ có khả năng giúp ta biết hợp quần, liên kết. Vẫn nội dung hai bài thơ sáu và tám câu trên đây, người đọc thấy văng vẳng đâu đó một lời mời gọi những con người còn có lương tâm phải hợp quần, phải chung lưng đấu cật để cùng nhau làm một cái gì hầu xóa tan đi cái thảm trạng những mái đầu xanh bị đọa đày một cách bất nhân, vô đạo. Là những người đang sống giữa một xã hội văn minh, dân chủ, tự do, chúng ta thấy tuổi thơ được tôn trọng, bảo vệ như thế nào.

Chính từ cảm nhận ấy, những lời thơ gọi là “trần trụi, đơn sơ” trên đậy của cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện quả thật đã có tác dụng liên kết mọi người thành một khối, biết gác ngoài mọi tư kiến, tư hiềm để cùng dấn thân vào một cuộc vận động chung hầu xóa tan đi những cảnh tượng đau lòng mà những ai còn có lương tâm, biết nghĩ tới tương lai quốc gia dân tộc không thể làm ngơ.

Bằng cái nhìn và lối suy nghĩ chủ quan, tôi rất tâm đắc và đánh giá cao bài “Sẽ có một ngày…” trong thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục của cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Ngoài giá trị nhân bản hàm súc trong lời và ý thơ, nó còn hàm ẩn một khơi gợi, kích thích cho một cuộc hồi tâm, một chuyến trở về tập hợp bên nhau giữa bạn và thù, giữa những người đã bị những tháng năm dài chiến tranh, thù hận đẩy xa. Xin mời đọc lại toàn bộ bài thơ.

“Sẽ có một ngày con người hôm nay

Vất súng

Vất cùm

Vất cờ

Vất Đảng

Đội lại khăn tang

Đêm tàn ngày rạng

Quay ngang vòng nạng oan khiên

Về với miếu đường, mồ mả gia tiên

Mấy chục năm trời bức bách lãng quên

Bao hận thù độc địa dấy lên

Theo hương khói êm lan, tan vào cao rộng

Tất cả bị lùa qua cơn ác mộng

Kẻ lọc lừa

Kẻ bạo lực xô chân

Sống sót về đây an nhờ phúc phận

Trong buổi đoàn viên huynh đệ tương thân

Đứng bên nhau trong mất mát quây quần

Kẻ bùi ngùi hối hận

Kẻ bồi hồi kính cẩn

Đặt vòng hoa tái ngộ trên mộ cha ông

Khai sáng kỷ nguyên tã trắng thắng cờ hồng!

Tiếng sáo mục đồng êm ả

Tình quê tha thiết ngân nga

Thay tiếng “Tiến Quân Ca”

Và tiếng “Quốc Tế Ca”

… Là tiếng sáo diều trên trời xanh bao la!”

(1971)

Dĩ nhiên, những gì gói ghém trong những vần thơ tha thiết trên đây chỉ là mộng ước của tác giả, và cũng là mộng ước của mỗi người Việt Nam. Nhưng âm hưởng, tiết tấu hàm ngụ trong lời và ý thơ quyện vào không gian mờ ảo của khói hương nghi ngút có sức mạnh làm mềm những trái tim chai đá của những kẻ lạc đường, lâu nay bị lôi cuốn vào những tham vọng bất chính, trả lại cho đương sự những tình cảm thuần lương, chân thực, để còn biết bùi ngùi hối hận khi nghĩ về cơn ác mộng: người đối xử với người như loài lang sói!

Giữa cảnh đen tối, tuyệt vọng của lao tù, bệnh hoạn, người thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện mơ về một ngày nào đó, súng ống, vũ khí giết người, cờ quạt, Đảng, Đoàn… sẽ bị vất hết để cho những con người hiền lương tìm đến bên nhau, cùng thắp lại nén hương bên phần mộ người thân từng bị bỏ quên trong những năm dài chinh chiến, hận thù.

Cho dù ước mơ của tác giả chưa thành hiện thực, nhưng quả thật trong một chừng mực nào đó, ý tưởng tha thiết hàm ngụ trong bài thơ trên đây của ông đã có sức lay động lòng người mãnh liệt. Cách đây không lâu, thời gian nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện còn tại thế, chính ông và người đang viết những giòng này đã được nghe tâm tình của một người anh em từ trong nước ra thăm thân nhân ở Mỹ.

Lần đâu tiên gặp mặt tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục, mắt anh sáng lên một niềm vui. Anh công khai cho biết đã cùng bạn bè thân quen ở quốc nội đọc đi đọc lại đến thuộc lòng nhiều bài trong tập thơ của Nguyễn Chí Thiện trên mạng internet. Anh thấm thía chia sẻ nỗi lòng của tác giả gói ghém trọng bài “Sẽ có một ngày…” Nó là một trong những động cơ khiến cho anh và một số bạn bè anh, những đảng viên CS hoặc cảm tình viên của chế độ lâu năm, trong sớm chiều phải suy nghĩ và đặt lại những gì mình tin tưởng từ bao nhiêu thập niên qua.

Thi khả dĩ hưng

Thơ có khả năng giúp ta hưng khởi, phấn chấn. Nghiền ngẫm gần 500 câu thơ cảm khái của Nguyễn Chí Thiện trong trường thi Đồng lầy, người đọc không khỏi trạnh lòng. Đấy là toàn cảnh bức tranh ảm đạm vẽ lại tâm tình đớn đau, tuyệt vọng của người thơ trước cảnh tang thương thấm đẫm máu lệ của con người bị dìm ngập trong vũng lầy hôi thối, chết chóc của xã hội Việt Nam kể từ khi lá cờ máu lên ngôi. Dưới đây là vài trích đoạn.

“Ngỡ cờ sao rực rỡ

Tô thắm màu xứ sở yêu thương

Có ngờ đâu giáo giở đã lên đường

Hung bạo phá bờ kim cổ

Tiếng mối rường rung đổ chuyển non sông

Mặt trời sự sống

Thổ ra

Từng vũng máu hồng

Ôi tiếc thương một mùa lúa vun trồng

Một Mùa Thu nước lũ

Trở thành bùn nước mênh mông

Lớp lớp sóng hồng

Man dại

Chìm trôi quá khứ tương lai

Máu, Lệ

Mồ hôi

Dớt dãi

Đi về ai nhận ra ai

Khiếp sợ!

Sững sờ!

Tê dại!

Lịch sử quay tít vòng ngược lại

Thời hùm beo rắn rết công khai

Ngàn vạn đấu trường mọc dậy giữa ban mai

Đúng lúc đất trời nhợt nhạt

Bọn giết người giảo hoạt

Nâng cốc mừng thắng lợi liên hoan

…

Đạo lý tối cao ở xứ đồng lầy

Là lừa thày phản bạn

Và tuyệt đối trung thành vô hạn

Với Đảng, với Đoàn, với lãnh tụ thiêng liêng!

Hạt thóc hạt ngô phút hóa xích xiềng

Họa phúc toàn quyền của Đảng

…

Tôi vẫn ngồi yên mơ màng như vậy

Mặc cho đàn muỗi quấy rầy

Bóng tối lan đầy khắp lối

Không còn phân biệt nổi

Trâu hay người lặn lội phía bờ xa…”

Nhưng, giữa hoản cảnh đau thương, tăm tối, tuyệt vọng ấy, từ đâu đó vẫn ngời lên một tia sáng hy vọng giữa đồng lầy ô trọc, đủ sức đánh động, phấn khích lòng người:

“Chúng tôi tuy chìm ngụp giữa bùn đen

Song sức sống con người hơn tất cả

Trước sau sẽ vùng lên quật ngã

Lũ quý yêu xuống tận đáy đồng lầy

Huyệt chôn vùi mùa Thu Nhục Nhã là đây

Hè, Xuân sẽ huy hoàng đứng dậy…, “

Bởi vì:

“Người dân đã có thừa kinh nghiệm // Bạo lực đen ngòm trắng nhởn nhe nanh // Trại lính, trại tù xây lũy thép vây quanh // Song bạo lực cũng đành bất lực // Trước sự chán chường tột bực của nhân tâm // Có những con người giả đui điếc thầm câm // Song rất thính và nhìn xa rất tốt // Đã thấy rõ ngày đồng lầy mai một // Con rắn hồng dù lột xác cũng không // Thoát khỏi lưới trời lồng lộng mênh mông // Lẽ cùng thông huyền bí vô chừng // Giờ phút lâm chung // Quỷ yêu làm sao ngờ nổi // Rồi đây // Khi đất trời gió nổi // Tàn hung ơi, bão lửa trốn vào đâu? // Bám vào đâu? // Lũ chúng bay dù cho có điên đầu // Lo âu, phòng bị // Bàn bạc cùng nhau // Chính đám sậy lau// Sẽ thiêu tất cả lũ bay thành tro xám! // Học thuyết Mác-Lê, một linh hồn u ám?// Không gốc rễ gì trên mảnh đất ông cha // Mấy chục năm phá nước, phá nhà // Đã tới lúc lũ tông đồ phải lôi ra pháp trường tất cả // Song bay vẫn tiệc tùng nhật dạ // Tưởng loài cây to khoẻ chặt đi rồi // Không gì nghi ngại nữa! // Bay có hay đâu sậy lau gặp lửa // Còn bùng to hơn cà đề, đa // Những con người chỉ có xương da // Sức bật, lật nhào tung hết // Hoa cuộc sống // Đảng xéo dày mong nát chết // Nhưng mà không, sông núi vẫn lưu hương // Mỗi bờ tre góc phố, vạn nẻo đường // Hương yêu dấu còn thầm vương thắm thiết // Nếu tất cả những tâm hồn rên xiết // Không cúi đầu cam chịu sống đau thương // Nếu chúng ta quyết định một con đường // Con đường máu, con đường giải thoát // Dù có phải xương tan, thịt nát // Trong lửa thiêng trừng phạt bọn yêu ma // Dù chết chưa trông thấy nở mùa hoa // Thì cũng sống cuộc đời không nhục nhã // Thì cũng sống cuộc đời oanh liệt đã // Nếu chúng ta cùng đồng tâm tất cả // Lấy máu đào tươi thắm tưới cho hoa // Máu ươm hoa, hoa máu chan hòa // Hoa sẽ nở muôn nhà muôn vạn đóa // Hoa hạnh phúc tự do vô giá // Máu căm hờn, phun đẫm mới đâm bông // Đất nước sa vào trong một hầm chông // Không phải một ngày thoát ra được đó // Con thuyền ra khơi phải chờ lộng gió // Phá xích, phá xiềng phải sức búa đao // Còn chúng ta phải lấy sức làm bè // Lấy máu trút ra, tạo thành sông nước // Mới mong nổi lên vũng lầy tàn ngược // Nắm lấy cây sào cứu nạn trên cao // Tiếp súng, tiếp gươm bè bạn viện vào // Phá núi, xẻ mây đón chào bão lộng // Nếu có thể tiến vào hang động // Tiêu diệt yêu ma // Thu lại đất trời // Thu lại màu xanh // Ánh sáng // Cuộc đời // Chuyện lâu dài, sự sống ngắn, chao ôi! // Nỗi chờ mong thắm thiết mãi trong tôi // Tôi mong mãi một tiếng gì như biển ầm vang dội

…

Tôi lắng nghe

Hình như tiếng đó đã bắt đầu

Nhưng tôi hiểu rằng đó là tiếng của lịch sử dài lâu

Nên trời đêm dù thăm thẳm ngòm sâu

Dường như vô giới hạn trên đầu

Tôi vẫn nguyện cầu

Vẫn sống và tin

Bình minh tới

Bình minh sẽ tới…”

Lời thơ dồn dập, ý thơ lồng lộng, quyết liệt như bài hịch xuất quân, tạo nên nguồn hưng phấn bất ngờ cho người đọc.

Trong bài “Khi Mỹ chạy…” trang 238-239 thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục, sau hai câu mang âm hưởng một tâm sự buồn đau: “Khi Mỹ chạy bỏ miền Nam cho Cộng sản,

Sức mạnh toàn cầu nhục nhã kêu than!!!” Tiếp đó là những lời thơ có sức xuyên núi, phá thành, dù người viết đang sống “Giữa tù lao, bệnh hoạn, cơ hàn”, bởi vì:

“Thơ vẫn bắn và thưa dư sức đạn!

Vì thơ biết một ngày mai xa xôi nhưng xán lạn

Không giành cho thế lực yêu gian

…

Thơ vẫn đó, gông cùm trên ván

Âm thầm, thâm tím, kiên gan,

Biến trái tim thành ‘Chiếu Yêu Kính’ giúp nhân gian,

Tất cả suy tàn,

Sức thơ vô hạn

Thắng không gian và thắng cả thời gian

Sắt thép quân thù năm tháng gỉ han!”

(1975)

Và vẫn những lời thơ bốc lửa, phấn khích như thế, trong hai bài “Đảng đày tôi…” trang 222 và “Trong bóng đêm…” trang 249 Hoa Địa Ngục, người thơ đã truyền vào hơi thở vào huyết quản, vào tâm não người đọc ông một ý chí quật cường, một tinh thần hăng say, quyết liệt, bứt phá, để trong một giây xúc động tột cùng, dám hy sinh tất cả để mong làm một cái gì, chống lại những thế lực hung tàn, ác độc để cứu nguy dân nước.

“Đảng đày tôi trong rừng

Mong tôi, xác bón từng gốc sắn

Tôi hóa thành người săn bắn

Và trở về đầy ngọc rắn sừng tê

Đảng dìm tôi xuống bể

Mong tôi, đáy nước chìm sâu

Tôi hóa thành người thợ lặn

Và nổi lên ngời sáng ngọc châu

Đảng vùi tôi trong đất sâu

Mong tôi, hóa bùn đen dưới đó

Tôi hóa thành người thợ mỏ

Và đào lên quặng quý từng kho

- Không phải quặng kim cương hay quặng vàng chế đồ nữ trang xinh nhỏ

Mà quặng uranium chế bom nguyên tử!!!”

(1972)

“Trong bóng đêm đè nghẹt

Phục sẵn một mặt trời

Trong đau khổ không lời

Phục sẵn toàn sấm sét

Trong lớp người đói rét

Phục sẵn một đoàn quân

Khi vận nước xoay vần

Tất cả thành nguyên tử!”

(1976)

Nếu Khổng Tử tái sinh lúc này hẳn ngài không thể không gật đầu, vuốt râu tâm đắc khi đọc những vần thơ hùng tráng trên đây của nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, vì hơn hết thảy, nó là biểu chứng rành rành cho định nghĩa “thi khả dĩ hưng” của ông.

Thi khả dĩ oán

Thơ có khả năng giúp ta biết oán hận. (Dĩ nhiên là những khi có nhu cầu phải oán hận, phải phẫn nộ để bảo toàn nhân cách, nhất là trong trường hợp đối tượng của oán ghét, phẫn hận là sự ác, gây tổn hại tới nhân quyền, nhân phẩm và sự sống con người.)

Có thể đoan quyết mà không sợ sai lầm là gần như mỗi câu, mỗi bài thơ của cố thi sĩ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đều gợi lên những tình cảm oán hờn, phẫn nộ trong ta. May mắn được quen thân và gần gũi tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục trong nhiều năm, cá nhân tôi nhận ra ở ông một nhân cách lớn, một con người có tâm hồn nhân bản, luôn bao dung, khoan thứ, chan hòa lòng yêu thương. Nó biểu hiện tròn đầy trong cung cách suy nghĩ, hành sử của ông trong đời sống ở bất cứ giai đoạn, cảnh ngộ nào. Cần xác định như vậy để chúng ta hiểu con người thật của Nguyễn Chí Thiện ngay cả khi đọc được những lời thơ bỗ bã, trần trụi, có thể nói là độc địa của ông chĩa vào đảng cộng sản, chủ nghĩa cộng sản và những khuôn mặt biểu tượng cho thứ chủ nghĩa tàn độc, phi nhân bản này.

Mời độc giả đọc lại hai câu đầu trong mỗi khổ bốn câu của bài thơ “Đảng đày tôi” ở trên để thấy đảng cộng sản đã xếp loại ông vào hạng kẻ thù hàng đầu cần truy diệt:

“Đảng đày tôi trong rừng

Mong tôi, xác bón từng gốc sắn!”

“Đảng dìm tôi xuống bể

Mong tôi, đáy nước chìm sâu!”

“Đảng vùi tôi trong đất sâu

Mong tôi, hóa bùn đen dưới đó!”

Đọc lại tiểu sử tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục, người ta được biết căn nguyên khiến Nguyễn Chí Thiện bị cộng sản tống ngục lần đầu ở lứa tuổi đôi mươi chỉ vì khi nhận lời dạy thế môn sử cho một người bạn ông đã mạnh dạn, thẳng thắn chỉ ra những chi tiết gian dối trong sách giáo khoa của chế độ Hà Nội(2). Kể từ đấy cho tới năm 1991, chỉ trong vòng ba thập niên, ông đã phải ở tù 27 năm dài không xét xử, không bản án, bao gồm cả chục năm bị hành hạ tàn nhẫn dưới chế độ kiên giam, tay chân bị cùm kẹp ngày đêm.

Bài “Xưa Lý Bạch…” một mặt vẽ lại cho người đọc thấy tâm tình và cảnh ngộ tang thương, khốn khó của tù nhân lương tâm Nguyễn Chí Thiện. Mặt khác nó còn là một bản đối chiếu giúp công luận nhận ra một sự thật khó tin là vào những năm cuối của thế kỷ 20, con người –kể cả thành phần ưu tuyển là nhà văn nhà thơ- dưới nanh vuốt của chế độ độc tài độc đàng cộng sản bị đối xử còn tàn tệ hơn cả thời phong kiến xa xưa:

“Xưa Lý Bạch, ngửng đầu nhìn trăng sáng

Rồi cúi đầu thương nhớ quê hương

Nay tôi, ngẩng đầu nhìn nhện giăng bụi bám

Và cúi đầu giết rệp, nhặt cơm vương

Lý Bạch rượu say gác chân lên bụng vua Đường

Tôi đói lả gác lên cùm gỉ xám

Lý Bạch sống thời độc tôn u ám

Phong kiến bạo tàn chẳng có tự do

Còn tôi sống thời cộng sản ấm no

Hạnh phúc tự do, thiên đường mặt đất

Rủi Lý Bạch, mà may tôi thật!”

(1967)

Trở lại với nội dung trường thi “Đồng lầy”, người đọc tìm thấy hàng trăm dẫn chứng về khả năng khơi gợi tình cảm “oán than, phẫn nộ” trước nỗi oan khiên mà đồng bào ta đã phải chịu trong hơn nửa thế kỷ qua, trong đó tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục là một điển hình bi đát. Để khỏi mất công tìm kiếm, mời quý vị đọc lại trích đoạn đầu trong trường thi “Đồng lầy” ở phần trên để cảm nhận tất cả nỗi đau đớn, uất nghẹn của con người bị bủa vây, cùm kẹp trên đất nước ta kể từ ngày chủ nghĩa cộng sản tràn vào.

Bài “Anh gặp em…”, trang 129 Hoa Địa Ngục, được nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện phô diễn lại hình ảnh tội nghiệp của người con gái miền Nam, khi đất nước bị chia đôi vào năm 1954, vì nhẹ dạ nghe lời dụ dỗ đã bỏ quê hương bản quán tập kết ra Bắc, để đến nỗi thân tàn ma dại khi đảng và chế độ đẩy vào vòng lao lý. Nội dung và âm hưởng hàm súc trong bài thơ này của cố thi sĩ họ Nguyễn gói ghém trọn vẹn tất cả bốn tiêu chuẩn Quan, Quần, Hưng, Oán theo cách nhìn về sứ mạng thi ca của người xưa.

Thứ nhất, bài thơ phơi bày trọn vẹn trước mắt ta hình tượng thảm thương, rách nát, ốm o, bệnh tật và cuối cùng là cái chết đau đớn, cô đơn của cô gái vì lỡ lầm chọn con đường tập kết từ Nam ra Bắc để trở thành tù nhân “bất đắc dĩ” của một chế độ bất nhân! Từ đấy cũng toát lên nhân cách và con người nhân bản của tác giả Hoa Địa Ngục.

Thứ hai, thứ ba rồi thứ tư, xuyên qua những nét chấm phá trên đây của người thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện, những tiếng nói thầm câm hàm ngụ trong bài “Anh gặp em…” đã có tác dụng nối kết những người Việt Nam yêu nước thương nòi lại để tác động, phấn khích lẫn nhau, khơi gợi thất tình, biết căm thù, oán giận, phẫn nộ, biết ngẩng cao đầu trực diện với sự ác, ngõ hầu kiên vững một niềm tin vào nguyên lý bất di dịch là “đạo nghĩa tất thắng gian tà”, sớm hay muộn, chắc chắn “Bình minh tới // Bình minh sẽ tới”.

Bình minh của mỗi cá nhân và bình minh của toàn thể dân tộc.

“Anh gặp em trong bốn bức rào dày,

Má gầy, mắt trũng

Phổi em lao

Chân em phù thũng

Gió lạnh từng cơn rú qua thung lũng

Em ngồi run

Ôm ngực còm nhom

Y sĩ công an

Nhìn em

Thôi nạt nộ om sòm(3)

Em ngồi lọt thỏm

Giữa bọn người vàng bủng, co ro

Những tiếng ho

Những cục đờm màu

Mái tóc rối đầu em rũ xuống

Mình em

Teo nhỏ, lõa lồ!

Em có gì đâu mà em xấu hổ!

Em là đau khổ hiện thân

Ngấn lệ đêm qua còn dấu hoen nhòa

Trên gò má tái

Trong lòng anh bấy nay xám lại

Nhìn em

Lệ muốn chảy dài

Anh nắm chặt bàn tay, em hơi rụt lại

Em nhìn anh,

Mắt đen tròn, trẻ dại

Nước da xanh tái thoáng ửng màu

Trong quãng đời tù phiêu dạt bấy lâu

Đau ốm một mình tội thân em quá!

Chắc đã nhiều đêm em khóc như đêm qua

Khóc mẹ

Khóc nhà

Khóc buổi rời miền Nam thơ ấu

Chân trời hun hút nay đậu?

Rồi đây

Em nằm dưới đất sâu

Em sẽ hiểu một điều

Là đời em ở trên mặt đất

Đất nước đè em

Nặng chĩu hơn nhiều!

Những lúc nghĩ thân mình bó trong manh chiếu

Anh biết lòng em kinh hãi hơn ai!

Khi gió bấc ào ào qua vách ải

Những manh áo vải

Tả tơi!

Vật vã!

Vào thịt da

Em có lạnh lắm không?

Mưa gió mênh mông

Thung lũng

Sũng nước bùn

Bệnh xá mối đùn, ẩm mốc

Những khuôn mặt xanh vàng gầy dộc

Nhìn nhau

Đờ đẫn không lời

Nhát nhát em ho

Từng miếng phổi rụng rời

Bọt sùi, đỏ thắm!

Em chắc oán đời em nhiều lắm

Oán con tàu tập kết Ba Lan

Trên sóng năm nào

Đảo chao

Đưa em rời miền Nam chói nắng

Sớm qua ngồi, tay em anh nắm

Muốn truyền cho nhau chút tình lửa ấm

Mặc bao ngăn cấm đê hèn

Sáng nay em

Không trống

Không kèn

Giã từ cuộc sống!

Xác em dấp trên đồi cao gió lộng

Hồn anh trống rỗng!

Tả tơi!”

(1965)

Bài thơ chấm dứt bằng mấy chữ trống rỗng! tả tơi! dội lên trong hồn người đọc một niềm cảm thương chất ngất pha lẫn hận thù. Cảm thương cho thân phận xấu số của người con gái sinh bất phùng thời. Cảm thương cho mấy chục triệu đồng bào đang gặp cơn ma chướng mà những gì chụp xuống thân phận tù nhân lương tâm Nguyễn Chí Thiện trong suốt 27 năm trường là một minh chứng. Từ niềm cảm thương được nối kết trong tình tự dân tộc ấy, một cơn oán hận ngút ngàn bùng phát trong tim óc mọi con dân Việt Nam trước dã tâm và những hành vi ác độc của chủ nghĩa bạo tàn cộng sản.

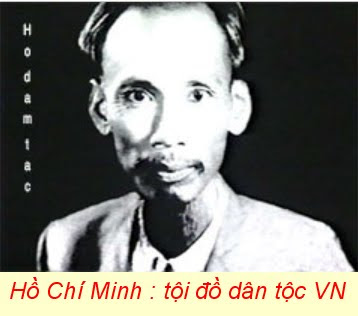

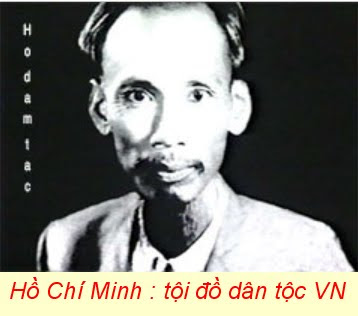

Ai? Kẻ nào đã đem chủ thuyết Mác-Lê vào gieo rắc tang thương, máu lệ trên quê hương ta? Nguyễn Chí Thiện là người đã chọn ở lại miền Bắc sau tháng 7 năm 1954 khi đất nước bị chia đôi. Nhưng cũng chính ông là người đầu tiên đã sáng suốt nhận ra không ai khác hơn là Hồ Chí Minh để công khai lên án y là “tội đồ dân tộc”, kẻ mà cho đến nay, mặc dù đã chết rục xương hơn 40 năm trước, vẫn còn được những đồ tử đồ tôn của y coi như thần tượng, là một thứ “cha già” để làm chỗ dựa lưng cho chế độ.

Ngay từ năm 1964, khi họ Hồ còn ở ngai quyền lực, nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã viết bài “chửi” thậm tệ nhân sinh nhật ông ta. Theo ông, Hồ Chí Minh chỉ là thứ “Chính trị gia sọt rác”, vì thế không xứng đáng để ông “Đổ mồ hôi… làm thơ” cho dẫu là làm thơ để “chửi”. Giữa thời vàng son của chế độ, giữa lúc thịnh thời của một kẻ đang được đảng và nhà nước xưng tụng, tâng bốc là “Cha Già Dân Tộc”, thế mà khi kết thúc bài thơ nhân sinh nhật “Bác”, Nguyễn Chí Thiện dám bạo tay viết ba chữ “Kệ cha Bác!”

Chưa hết, bốn năm sau, năm 1968 cũng là năm Hồ Chí Minh chết, nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã hạ bút viết “Không có gì quý hơn độc lập, tự do”, câu nói từng được thốt ra từ cửa miêng họ Hồ để mở đầu cho một bài thơ bất hủ của ông. Trong bài này, tác giả đã dùng những danh xưng “xách mé” để chỉ họ Hồ, kẻ mà ngay từ buổi bình minh của chế độ đã huênh hoang phát ngôn như thế. Ông minh nhiên gọi Hồ Chí Minh là “nó”, là “thằng.” (Tò mò đếm thử, người ta đọc được trong bài thơ 54 câu, ngoài một chữ “thằng”, Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã dùng tới 32 chữ “nó” để chỉ danh tính Hồ Chí Minh).

Như đã nói ở trên, ngày nay khi nhân loại đã khởi sự bước vào thập niên thứ hai của đệ tam thiên niên, dù họ Hồ đã về với tổ sư Karl Max của ông ta, đảng và nhà nước CSVN vẫn tiếp tục sơn phết xưng tụng, coi y như một thứ thần tượng, và kể cả những phần tử phản tỉnh vẫn chưa dám trực diện nói động đến y. Có hiểu như vậy chúng ta mới thấy được hết sự căm hận của nhà thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đối với chủ nghĩa cộng sản như thế nào. Từ mối căm hận đến tận xương tủy ấy, nhà thơ họ Nguyễn đã trút hết tất cả nỗi bực tức và cơn phẫn nộ ngất trời của ông lên kẻ “tội dồ dân tộc” là Hồ Chí Minh.

Hơn tất cả, từ cách dùng ngôn từ một cách bỗ bã, bộc trực cho tới lối vận dụng, nối kết ý tưởng trong thơ, tác giả đã khơi gợi được trong lòng người đọc một nỗi hờn oán, phẫn nộ thật chính đáng khiến mọi người mặc nhiên đồng thuận với người thơ khi nhận chân được bộ mặt giả nhân giả nghĩa, hoàn toàn lệ thuộc ngoại bang để công khai có những hành vi hèn với giặc ác với dân của họ Hồ, qua những động thái của thân phận tôi đòi “Lúc rụi vào Tàu // Lúc rúc vào Nga // Nó gọi Tàu, Nga, là cha anh nó // Và tinh nguyện làm con chó nhỏ // Xông xáo giữ nhà, gác ngõ cho cha anh”!!!

Để độc giả khỏi mất công mở Hoa Địa Ngục, xin ghi lại toàn văn bài thơ sau đây:

“Không có gì quý hơn độc lập tự do

Tôi biết nó, thằng nói câu đó

Tôi biết nó, đồng bào miền Bắc này biết nó

Việc nó làm, tội nó phạm làm sao?

Nó đầu tiên đem râu nó bện vào

Hình xác lão Mao lông lá

Bàn tay Nga đầy băng tuyết giá

Cũng nhoài qua lục địa Trung Hoa

Không phải xoa đầu mà túm tóc nó từ xa

Nó đứng không yên

Tất bật

Điên đầu

Lúc rụi vào Tàu

Lúc rúc vào Nga

Nó gọi Tàu, Nga, là cha anh nó

Và tình nguyện làm con chó nhỏ

Xông xáo giữ nhà, gác cửa cha anh

Nó tận thu từ quả trứng, quả chanh

Học thói hung tàn của cha anh nó

Cuộc chiến tranh chết vợi hết thanh niên

Đương diễn ra triền miên ghê gớm đó

Cũng là do Nga giật, Tàu co

Tiếp nhiên liệu, gây mồi cho nó

Súng, tăng, tên lửa, tàu bay

Nếu không, nó đánh bằng tay?

Ôi đó, thứ độc lập không có gì quý hơn của nó

Tôi biết rõ, đồng bào miền Bắc này biết rõ

Việc nó làm, tội nó phạm ra sao

Nó là tên trùm đao phủ năm nào

Hồi Cách Mạng đã đem tù, đem bắn

Độ nửa triệu nhân dân, rồi bảo là lầm lẫn!

Đường nó đi trùng điệp bất nhân

Hầm hập trời đêm nguyên thủy

Đói khổ dựng cờ Đại Súy

Con cá, lá rau nát nhầu quản lý

Tiếng thớt, tiếng dao vọng từ hồi ký

Tiếng thở, lời than, đem họa ụp vào thân!

Nó tập trung hàng chục vạn “ngụy quân”

Nạn nhân của đường lối

“Khoan hồng chí nhân”của nó

Mọi tầng lớp nhân dân bị cầm chân trên đất nó

Tự do, không thời hạn đi tù!

Mắt nó nhìn ai cũng hóa kẻ thù

Vì ai cũng đói mòn, nhục nhằn, cắn răng tạm nuốt

Hiếm có gia đình không có người bị nó cho đi suốt(4)

Đất nó thầm câm cũng chẳng được tha

Tất cả phải thành loa

Sa sả đêm ngày ngợi ca nó và Đảng nó

Đó là thứ tư do không có gì quý hơn của nó!

Ôi, Độc Lập, Tự Do!

Xưa cũng chỉ vì quý hai thứ đó

Đất Bắc mắc lừa mất vào tay nó!

Thế mà nay vẫn còn có người mơ hồ nghe nó

Nó mới vạn lần cần nguyền rủa thực to

(1968)

Lời cuối - Dù chỉ làm công việc sờ voi, mới lướt qua và lược trích một phần rất nhỏ trong số 700 bài trong thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục, người viết trộm nghĩ rằng:

thơ Nguyễn Chí Thiện đã gói trọn được tôn chỉ Quan, Quần, Hưng, Oán theo quan điểm của Khổng Tử. Điều này dễ hiểu. Trước hết, vì ông là một nhà thơ có chân tài. Và tài năng siêu đẳng ấy đã chắp cánh cho thơ ông bay cao nhờ lòng yêu nước, thương dân cao như núi, dài như trường giang và sâu rộng như biển cả.

Tất thảy đã trang bị cho ông một khối óc siêu phàm, một cặp mắt tinh tế, một trái tim bén nhạy, biết thương cảm trước nỗi khổ đau của con người và biết biện phân thiện ác, chân giả giữa một xã hội điên loạn, gian manh, trí trá của một miền Bắc Việt Nam bị áp đặt dưới chế độ bạo tàn cộng sản với một bộ máy cầm quyền được điều hành bởi những kẻ bất nhân, vô đạo mang những trái tim bằng đá.

Rất nhiều lần Nguyễn Chí Thiện công khai xác nhận ông không phải là người hùng. Trong Lời Tựa thi phẩm Hoa Địa Ngục, ông từng viết:

“Tôi cố lên gân, nhủ mình phải có khí phách anh hừng. Nhưng vì trong máu không có một tí chất anh hùng nào cả… nên lâm vào cảnh: ‘Năm rồi năm, trời đất mịt mùng // Khí phách anh hùng rũ lả’”